Axis & Allies

Serializing

Damo Bullen’s

Epic poem

AXIS & ALLIES

Throughout 2024

In 85 Cantos

Preface

What has been may be again: another Homer, & another Virgil, may possibly arise from those very causes which produced the first

John Dryden

Axis & Allies has been the work of my life. Beginning in Brighton, 1999, it has both escorted & driven me across the planet in the pursuit of its creation. Four years ago, on the Greek island of Samothraki, I thought I’d formally completed the poem, as I saw it then, & as this video attests;

An Olympiad later, or so, I shall be resuming my task, focusing this year on the central cantica, concerning the build up to, & the actualisation of, the Second World War. This video shows me at the very start of the poem’s latest composition period;

This next video was filmed January 18th, 2024, & shows me adding flavour to the stanza notes from events 1930-36.

The next video was film’d just a few days before the start of the Chinese new year (I’m a Fire Dragon)

The next video was film’d in Arran on the day I finalised the poem’s architectronics

Each week there will be two new cantos, out of 85 in total,

Uploaded onto Mumble Words

Enjoy !!

x

Damo

(AA) L’Amfiparnasso

So arose the practice of celebration in exalted verse the battles & other notable deeds of men, together with those of the gods.

Boccaccio

Invocation

Something has broken in the mouths

of the young men on earth

Our thoughts fails us, we are made poor

Arthur Yap

There is a glade in an ancyent forest

Where glittering pools of dewy azure

Assail ripe sense… insliding, moonbeam-bless’d,

Soul bathes in blissful dreamtime gleaming pure;

Attended by

My nine naked maidens,

Vulvaean lullaby lilting thro’ Love’s gardens.

She harps a song, she summons stars,

She waltzes round the waters,

She treats these sainted battlescars,

She paints a floating lotus,

She strums her summergold guitars;

Loxianic daughters!

How lovely & how livid floods thy light,

What verses & what wonders must I write?

They ring & weave thro’ tryptych tones,

Sing rich enchanted chime,

Soft music hones their mystic moans,

& so… my all must rhyme…

With hopes of flashing heroes up Parnassus slopes we’ll climb!

To My Readers

he had worn out his teeth

on the locks of ancient gates.

On the most out-of-the way paths

Ahmad Shamlu

I know these words rest heavy in the hands,

When reading them should heap a little while,

But think of me alone in distant lands,

With heavy load, abroad an extra mile;

Thro’ thorn, up steep,

In search of awesome views,

Where I would sit in deep communion with the Muse.

Gadswounds! My global chronicle

Will preserve the violent show

Of our planet’s lust for battle,

Men panting for Megiddo;

Friends! Be ready for to Google

All words ye do not know,

When mining into human history,

This is a kind of University!

Prepare a bath, pour out your wines,

Light up a candle’s flame,

Encase your minds, embrace these lines,

Enlightenment our aim,

War’s business is but terrible – not glory, nor a game.

Impulses

Unleash a poem slow enough,

Fie with vigilance & care

& you’ll discover lots of stuff

Don Paterson

I sing of Mars, whose blood-besplatter’d reign

Lived long among the secret brotherhoods,

& if these verses vast mine aim deem plain:

To elevate auld lives before the Floods;

When to the stars,

Or in our upmost caves,

This exile song of Mars an epic epoch saves.

As the vestige Villanovan

Found in Verruchian tombs,

As golden-thron’d Glasgerion

Immortalis’d ladies looms,

Ready, my lithe young mind…. Open!

When poetry resumes,

I’ll pay the World its histrionic dues,

Quite polyamorous to every Muse.

Non sono nazifaschisti,

Fair freedoms forged in blood,

The mystery of history

Spreads thro’ me like a wood,

In which I’ll twist unfettered feet as only Clio could.

Valedictions

I should invent my own speech

and leave others empty and afraid

that they did not know it, could not ask

Ricardo Pau-Llosa

I am no pickpurse of another’s wit,

Yet understand tradition is a tool,

When mostly I’m the Muses’ conduit

& sing to them, prostrately, as a fool,

“Je suis rien,

Per je ne suis pas dieu,

Vous etes tout mon bien, le lustre de mon cieux!”

As when old Thales’ Iliad

By princely rhapsodes utter’d,

The ghosts behind these lines glow glad

Whenever they’ll be mutter’d,

As if some new Upanishad

Down the Deccan flutter’d,

Containing all the epos of an age,

Far from the sterile tombstone of the page.

As when elders Albanian

Sang legends kith & kin,

Or Suqatran, hoary herdsman

Harps word-hordes held within…

Verse-vestibules of history maintain Cruachan’s Djinn!

Arcadia

A beggar at the crack of dawn comes with

an empty cup, just as a line of monks

serenely with their bowls set out for alms

Saksiri Meesomsueb

Always preparing, always reparing,

The new ensemble of a Danaan song;

No single impulse, but many sharing,

A swirl of verse, a whirl of words among

Eternal heights

Of endless mountenance:

Criss-crossing cloudless nights wild woodland swans advance!

With Saint John & the Patmos vine,

The Bard of the Scyldingas,

Dante’s Commedia Divine,

Tasso’s inspired Crusaders,

With Spenser’s store of faerie wine

& Milton’s masterclass,

I made my bed – from patchwork eiderdown,

I pluck’d my quills & ink’d them up in town!

From erudition constancy

To genius applies;

Consistency, coherency,

Watch phaerie wonders rise

From paranormal mutterings… them given golden guise.

Astrophel

into a world

waiting like

a quiet lover

Max Reif

I stretch to grasp the gross Orphean lyre,

These fingers on the fringe with fuga fraught,

When en-plein-air whisp’ring perfumes transpire,

Hyblean murmors of prophetic thought;

Beside Mankind

I find my social niche,

Reflective & refined; the poesy of pastiche.

Along the road I drank my wine,

While others gave it gladly,

Good souls were they, old friends of mine,

Such thanks to all who’ve had me,

Some tickl’d by this soul-sunshine,

Others flummox’d madly,

For poets & their strangely ancyent ways

Are meant to men affix… affront… amaze.

As from the Wealth of Nations rise

A pleasure-loving soul,

Invested ties friendship supplies

Up puff me proud & tall,

To conjure something rich & queer to steer us, each & all.

Testamundi Poeticus

And if there’s something that remains

Through sounds of horn and lyre,

It too will disappear into the maw of time

Gavrila Romanovich Derzhavin

I am a man, many have gone before

& will come yet; to thee I trust this song,

Pray let her fly to every foreign shore,

Shewing the World how once the World went wrong;

Such manic times

Have ended, only just,

Whose freshness fills these rhymes far from the bookish dust.

I would the World should hear this song

& sing her down the ages,

So, when the epic, proud & long,

Renaissance ever stages,

Let poets ply their trade among

Polytechnic pages,

Finding a thing or two that they could use

In future conversations with the Muse.

Namore shall Homers chaunt War’s praise

Or Owens curse it’s game;

Some psychic craze, unbridl’d days,

Crude torture, quelling shame,

This is my long-wrought testament to what Mankind became.

Avanti!

I am not a mirage, but a being in flesh

Born of a sea that has neither

Waves nor shore, nor moon, nor star

Horace Gregory

When two traditions meet in epic song,

There history & poetry converge

Upon a point called nexus, whence among

Man’s consciousness progressive senses merge;

Tilling the soil,

Planting these sapling shoots,

Which over time uncoil as fields of figs & fruits.

So grow, ye lotus-burnish’d gold,

Ye zest-infested lemon,

Go store these tales of glories old

For future to look back on,

Five thousand years must now unfold

Before this age is run;

Half-way, of course, some Homer might arise

& half-an-age in poesy realize.

Asoka’s edicts I have seen

War’s monuments may you,

Days pass’d have been disturb’d, obscene,

But from the gore their grew

This peaceful pearl, this precious planetary parvenu!

Aquarians

Buried was the dreadful war-club,

Buried were all warlike weapons,

And the war-cry was forgotten

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

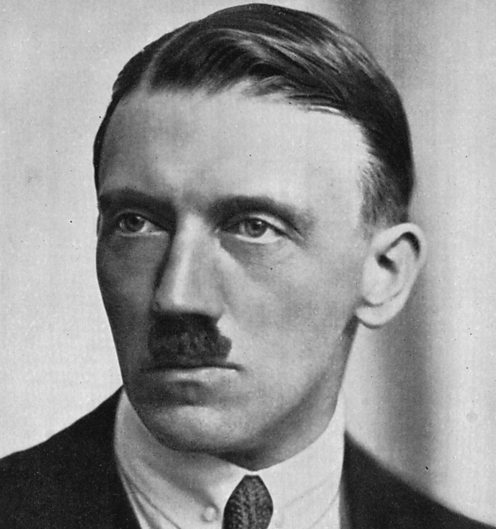

We’ll all look back on Us with pure disgust,

How on Earth did we let Hitler happen?

Lest we forget his deeds, with thee I trust

These tryptychs prim’d on a cryptic pattern;

Homeric horn,

Of perpetuity,

To thrill, to teach, to warn, through all futurity!

Beyond the threshfold of warfare

As fought by brave Achaean,

To atom-splitting solar flare

Flung from the North Korean,

The threat of death the World would share;

Bodies block the Scaean –

Unnumber’d, multitudinous, immense –,

How many lives are robb’d of innocence?

Like amaranth anemones

This book of rumbling words,

Mnemones & melodies,

Midst lines of waltzing thirds,

Must shimmer ever phosphorous as if t’were sufi birds.

(AA) Canto 1: Broken Peace

Armistice

And view with retrospective eye

Th’Imperial States whose awful destiny

It was to fade, decay, & disappear

Count Frederick Von Erlach

The War is over, namore the killing,

Meek Franciscans move thro’ many nations,

HOPE mops blood-sodden brows, when, god willing,

All countries & creeds breed good relations;

Order’d to yield,

The Wehrmacht leave the trench,

Behind, a bitter field & the ecstatic French.

The Hohenzollern dynasty

Emulates the ancyent Czar,

Forfeits the Kaiser’s monarchy

To the fortunes lost in war,

The Junkers of old Germany

Gathering at Weimar,

Shall delegate a democratic air,

A treacherous republic to declare.

In some disused railway carriage

All honour sign’d away,

A fretful page, a flaming rage,

To burn some bitter day,

When rise once more shall Germany, when all the world shall pay.

Forest of Compeigne

November 11th

1918

Hitler Awakes!

Indeed the idols I have loved so long

Have done my Credit in Men’s Eye much wrong :

Have drown’d my honour in a shallow cup

Edward Fitzgerald

Far from the front rested little Hitler,

Bed-stricken with a bout of syphilis,

Into the ward bursts a babbling pastor,

“Friends, we are beaten, there’s an armistice!”

The war was lost,

As fury rakes the room,

Into a sea-storm toss’d souls suffering in gloom.

He struggl’d to his feet in pain,

Rush’d pass’d the shell-shock’d patients

Into an evening’s winter’s rain,

Cursing the western nations,

“Is all our sacrifice in vain?

All our bleak privations?”

How could this be, he’d sens’d it in his core,

Herr Hitler was a superman of war.

Slump’d by rain-swept roadside seated,

Sobbing for Germany,

His depletedly defeated,

Yet wunderbar contree,

He felt brave future’s grooming to assume his destiny.

Pasewalk

November

1918

Flight of Peace

Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll !

Leave thy low-vaulted past !

OW Holmes

Where once was warring calm must reign supreme,

When analysts can encase all the data,

Oer Saharan hues, cerulean dream

Dovelets flew, ellipsing the Meseta;

Dog-rough cloud rolls

Inspiral from the Earth,

Lest we forget those souls who sacrificed their birth.

The tumult & the shouting dies,

The world three armies receives,

The first with murder in the eyes

When a wounded heart bereaves,

The next already on the rise

As good men become thieves,

Then pity the last! forced to bear the mark

Of battle… some crippl’d, some mad, some dark.

O slender bird, majestic mein,

Men watch ye as ye fly

Up over Spain & in thy train

Men made contented sigh,

Watching thee dance amid the burning tapers of the sky.

Europe

November

1918

English Salon

one more presentiment

where certainty is not hard to come by:

wing tips brush the face of the waters

Gottfried Benn

Men gather’d for Parisian soiree,

The leading lights of England, more or less,

Collected like a Bloomsbury bouquet

By Mary Borden, warden & hostess;

When, with war won,

Gone was the nervous strain,

Which flummox’d everyone like maggots in the brain.

Lloyd-George was there, his snow-white hair

Did flutter with the winces,

Winston would mutter with a stare

While one of nature’s princes

A garb of Arab robes did wear

“Moscow shan’t convince us,”

Splurts Churchill, “of their Bolshevik journey,

One might as well legalize sodomy!”

“Now of the Germans let us speak…”

“The Kaiser should be shot!”

“Let’s squeeze & tweak, ‘til pips do squeak

Their war debts ‘til we’ve got

Enough to pay off Washington & stave the Empire’s rot.”

Paris

January

1919

Soloheadbeg

Not in the clamour of the crowded street

Not in the shouts & plaudits of the throng

But in ourselves are triumph & defeat

Henry Longfellow

“Home rule is Rome rule”, the Six Counties say,

The rest of Ireland bounc’d back from the booths,

Sinn Fein land-sliding, biding ’til this day

Of souls exploding to their simple truths;

Ireland’s Ireland,

Let’s send the British home,

Still… Ulstermen won’t stand the slightest link with Rome.

As gelignite, by horse-drawn cart,

Trundles down a country lane,

Six rifles aim’d at head & heart,

Halts two soldiers in its train,

A moment’s madness made them dart

For cover, but were slain,

Whose deaths – before false warriors were blam’d –

The Irish Republican Army claim’d.

“Posters pasted like paper swords

Painting duty martyrs,

Promise rewards from London’s lords

& pardons meant to part us…”

“We’ve got ’em rattl’d lads, fuck their English Magna Cartas.”

Tipperary

Jan 21st

1919

Table Talk

Touch’d by this vastness

I ask the boundless earth;

Who after all will be your master

Mao Tse-Tung

Men gather’d for Parisian soiree,

The leading lights of England, more or less,

Collected like a Bloomsbury bouquet

By Mary Borden, warden & hostess;

Where, with war won,

Gone was the nervous strain

Which worried everyone like maggots in the brain.

Lloyd-George was there, his blizzard hair

Did flutter with the winces,

Winston mutter’d a lizard stare,

While one of nature’s princes

Wore robes the Arab wizards wear –

“Moscow shan’t convince us,”

Splurts Churchill, “of its Bolshevik journey,

One might as well legalize sodomy.”

“Now of the Germans let us speak…”

“The Kaiser should be shot!”

“Let’s squeeze & tweak until pips squeak

Her war debts, ’til we’ve got

Enough to pay off Washington & stave the Empire’s rot.”

Paris

February 1919

Homecoming

That, setting, the sun has only to highlight

Girls crowding the railway track, as the train slows,

For me to discover it is not my station

Boris Pasternak

At the Douamont fort, by sunset shades,

Lay veterans a wreath to heal Verdun,

Melancholic souls of fallen comrades

Escort one, living, back to Briancon;

Two hundred francs,

Two shirts, suit, shoes, no more;

With all a nation’s thanks for winning them the war.

Click-clack’d the slowly sloping train

Up thro’ the Alpine passes,

Attack’d by shawls of driving rain,

He wipes his misty glasses…

“At last! Mon coeur sees home again!”

Light & glossy lasses –

Like flutes, dribbling jubilant glucose –

Applauding nostoi of their handsome heroes.

He heads for home, he sheds a tear,

A gasp! “C’est Jean-Francois!”

Who, halting cheering, jolts back beer,

Drenching thirst in nectar,

“Deux francs,” “Deux francs! C’est ridicule pour une Stella Artois!”

France

March

1919

Spoils of War

No longer hosts encount’ring hosts

Shall crowds of slain deplore

They hang the trumpet in the hall

Michael Bruce

They came like Jackals to a wounded bear,

Reflected in the mirrors of the Hall

Men shone no souls – remorseless, unaware,

That what they will’d would build a gilded wall

Twyx world & peace,

This fog-drench’d vengeful clime,

When, who was there to police the intransigent crime

Of Germany’s reparations,

When memories of menace

Choke all cautious moderations –

Grunting hogs like top-tier tennis,

Carcass-tooth’d the delegations,

Concurring, say “When is

A conqueror unable to dictate

What crown or territory to mandate!”

On Berlin foists the guilt of war,

The peace branch but a twig,

That scratches sore, a corridor

Links Warsaw to Danzig –

The French entrenching with revanch, how deep the spurr’d heels dig.

Versailles

June 28th

1919

Returning Heroes

Goodbye my friend, without hand or word,

and don’t let sadness furrow your brow,

in this life dying is not a thing unheard

Sergei Yesenin

When Alister & Charles Glen Rosa reach,

Miraculously both twins had surviv’d

The war unscath’d, one day on Brodick beach

They took a picnic, felt they’d home arriv’d

Safe from the sights

Of body-bits in sacks

Of lives in sniper sights ‘tween suicide attacks.

What men the boys had all become,

Tensions ever simmering,

Jock wheel’d round Lamlash by his mum,

Jabber-gibbon gibbering,

& Douglas, ne’er without his rum,

Persistent pestering;

“I fought for you, & I lost my brother…

Those who’d stay’d at home bought him another.

Our twins stroll to their timeless glen,

Untouch’d by all the games

Of Gods & Men, Goat Fell was then

In green & orange flames

Lit by the sun, they sat scene-stunn’d, whispering dead friends’ names.

Arran

July

1919

(AA) Canto 2: Delegations

Reparations

Every bit of scrap iron sits

In the hall of the old manor,

And, on the wall, a shadow flits

Theophile Gautier

“Upon the sacred soil of Vaterland

No enemy had stepp’d a single foot,

Thus how audacious they are to demand

These reparations, slump us in a rut!?”

Poor Germany

Never might recover

As when two soul mates see their other with a lover!

Where shrunken, starving babies curse

The birth to which them fated

As once pure housewives fill their purse

Thro men’s lust satiated

A scapegoat sentence well rehears’d

“Let all Jews be hated,

Living luxuriously while we strive

Each day, in desperation, to survive.”

Six cases of the best Moet

Blackmarkets Ribbentrop,

Round cabaret, the play, ballet,

He tour’d his mobile shop,

Some handsome, dashing chancer somehow dancing to the top.

Berlin

August

1919

Broken Dreams

I have nae will to sing or danse

For fear of England & of France

God send them sorrow & mischance

Sir Richard Maitland

“Upon the sacred soil of Vaterland,

No enemy had stepp’d a single foot,

Thus how audacious are they to demand

Such reparations;” tuskers in a rut,

For Germany

Never might recover

As when two soul mates see each other with a lover.

As shrunken, starving babies curse

The birth that they were fated,

As once pure housewives fill a purse

Thro’ men’s lust satiated,

The scapegoat sentence well rehears’d,

“Let the Jews be hated,

Living luxuriously while we strive

Each day of desecration, to survive!”

Six cases of the best Moet,

Black-markets Ribbentrop,

Round plays, ballet & cabaret

He tour’d his mobile shop,

Some handsome, dashing chancer dancing, somehow, to the top.

Berlin

November 1919

Brave New World

Sleep, for the yards of jail houses

Are all teeming with violent death,

And you are the more in need of rest

Muhammad Mahdi Al-Jawahiri

“Let us establish a League of Nations,”

Say the wardens of a war-weary world,

Glimpsing Man’s maturer aspirations,

Now that his battle-banners have been furl’d;

The status quo

Returns to normalcy,

The nurse-child of Anglo-Saxon hegemony.

Britain proclaims pre-eminence,

Now Russia has revolted,

The moral laurels worn by France,

For ‘peace’ truly devoted,

But spurning this most perfect chance,

Ostrich isolated,

The Yanks withdraw yon oceanic moats,

Jealous of England’s empire’s six full votes.

On a simple piece of paper

‘World Peace’ has had its birth,

America’s non-signature

Belittling its worth,

Shirking responsibilities as policemen of the Earth.

Geneva

January 1920

War & Peace

I am the rustling of the world

the swaying between here and elsewhere

the dumb foliage of the cactus

Abdourahman A. Waberi

As the snarl of that Star-Spangl’d nation,

Which ended Europa’s love of violence,

Shrivels, daily, into isolation,

Two Philopoema, charg’d with their defence,

Nestle to eat

Pot hot, home-made dinner,

Fans wafting off the heat from a white veranda.

As Mrs Patton pours the wine,

The gentlemen wisdom share,

Drape musings with a southern whine,

On the art of Tank Warfare,

“To penetrate the foe’s front line

Swift as a grizzly bear

“Plucks salmon, strike, back’d by artillery,

Not hamper’d spread defending infantry.”

Once Mrs Mamie Eisenhower

Had serv’d the last liqueur,

A quick shower, within the hour,

They’ll start a smart lecture

On ‘Pursuit of Routing Armies,’ by a young MacArthur.

Camp Meade

September

1920

The Nazi Party

I cannot tell what ails me,

But this I know for sure,

Thou only art my cure

Baba Tahir

He took the stand before a growing band

Of misfits, bandits, madmen & chancers,

Enchants them with a panorama spann’d

Over time across epic expanses;

His voice rings loud,

Flush’d with higher German,

Binding demotic crowd to th’ypnotic sermon.

“For over fifteen centuries

Reign’d the Holy Roman law,

When Fate unites the Germanies

We shall speak the peace once more

& Versaille’s damned iniquities

Demolish with a roar!”

”Rubbish!” some quatted heckler dares a noise,

Dragg’d off, rough’d up by tough-mouth’d bully-boys.

All hail the hero of the right,

Staunch National Socialist,

Ready to fight by plebiscite

Thro politics & fist,

The decadent democracies… his horde applaud upryst.

Munich

December

1920

Baby Boom

Sometimes I can almost see, around our heads,

Like gnats around a streetlight in summer,

The children we could have

Sharon Olds

Charlie Sumner stagger’d down Accy Road,

Hit Havelock’s lock-in, a quick whiskey,

Then thro’ his crude two-up, two-down, tiptoed,

To pounce upon his wife, drunk & frisky;

“Gerroff!” a clout,

His silent smile’s intrigue

Bends to triumphant shout… “We’ve won the blummin’ league!”

How rare is it to find true mate

To share thy meagre ration,

Youths rush upstairs to celebrate,

Indulging perfect passion

Without a jonny, for, of late,

Babies are in fashion:

He gasps as he sighs as his seed slips in,

A cry! Rose rises, “Our Jack needs feedin!”

His wife away…. some charabang

Lets off a lively BOOM!

With barren pang the clammy clang

Of battle claims the room,

While friends that fell at Passcheandale wail, “Charlie!” thro’ the gloom.

Burnley

May

1921

Enchanted Land

water they needed

this morning when

the river was drying

Rina Garcia Chua

The Oppenheimer’s lov’d the holidays,

Whose Picassos hung at Riverside Drive,

Were nothing to the glorious haze

Of shimmering sun the day they’d arrive

Back at the ranch,

Hard by Albuquerque,

For barbies, branch-by-branch, jug-glugs of Wild Turkey.

Young Bobby donn’d a cowboy’s hat

Said to the ranchers, ‘let’s go,’

With native shaman sat to chat

& smok’d & tok’d each next go,

Then kinda stoned in silence sat

By Sangre de Cristo

Where lonely, wee Los Alamos appear’d

To strike some chord within him, fraught & weird.

He rode back home, where there did sit

Some letter forwarded,

So open’d it, a flapping fit!

‘Mom, I’ve been accepted,”

She rushes in; “Where is it?” “Ma” “What?” “I’m off to Harvard!”

New Mexico

June

1921

The Birth of Ulster

The cavalry flew by and vanished,

The storm thundered and hushed.

Lawlessness bore down, bore down

Mikhail Alekseevich Kuzmin

From powderkegs of possibilities,

Europa exploded with republics,

Enjoying the responsibility

Of self-determination – old dog tricks

Of sit, beg, stand,

Silenc’d, & forever,

Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Latvia!

Now Ireland wants a bit of that

Again, quite complicated,

As murder gangs go tit-for-that,

Assassins unabated,

The Black & Tans despising ‘Pat,’

Heinous & hated,

This crowded hour of Gaelic history,

Deals in dark death instead of liberty.

Partitioners accept the curse,

Imperial hybrid;

It could be worse, the public purse

No thirsty invalid,

For, to be fair, wealth everywhere blares what the British did.

Ireland

July

1921

Curiosity

a poet came,

lightly opened his lips,

and the inspired fool burst into song

Vladimir Mayakovsky

“The reason I have usher’d you here for,

Truman, is to find out information,”

Said the American ambassador,

“On a political demonstration,”

“Where, sir?” “Munich…”

“The Nazis?” “Yes…” “The place?”

“Cornelius Street, quick field check, y’know, just in case.”

Smith silent sits as Hitler stands

Above the hundertschaften,

Where ruffians in red armbands,

Men of lowly origin,

Goose-stepping slid to marching bands,

Twas such a raucous din,

That any tetratologist would think

Some creature-thing was shrieking at the brink.

Outslurr’d the Juden diatribe

From babbling, bubbling craw;

Thro’ jeer & jibe threats clear proscribe

The shirkers of the war,

Whose profiteering cowardice sets fires in the straw.

Munich

November 15th

1922

(AA) Canto 3: Saunterings

Reparations

She has been abandoned

She has been betrayed

God has betrayed her

Mary Borden

The muck of money – filthy, spreadable –

Fair fertilizer of economy,

But where inflation spews incredible

Even the richest lose autonomy;

In direst straits,

Deutschland holdeth no cards,

Owing the Western States marks by the milliards.

Well… Washington leant London dough,

Paris, too, which paying needs,

When hoping, both, to fend the blow

Springething from Human greeds,

“Here’s what you owe!” the beaten foe

Are told, “forget your needs…”

Berlin, alas, unable to conduct

A single cent per dollar – purely fuck’d!

With swaggerstomp the French explode

All oer the Ruhr’s coalfield,

Send, load-by-load, back home, abroad

The Rhineland’s vital yield,

A vicious sleight of victory which VENGEANCE aches to wield.

Dortmund

January 11th

1923

Putsch

Who is this screamer in the street?!

With a frightened voice and broken heart

Who is this mad man?!

Ali Khalifa

Minacious voice yelling, “Now is the time!”

Bullies into the Beurgerbraukeller,

Bemedall’d Ludendorf lending his crime

A strange respect – that dangerous fella,

Unfash’nable,

Leaps up, shooting his gun,

“Countrymen the national revolution’s begun!”

While Roehm mans up the Ministry,

Hitler’s phrenzied followers

Steam enteric thro’ the city –

Trucks of singing stormtroopers-,

To ringing Rathaus chivalry,

Down Residenstrasse’s

Streets to the Odeonsplatz… in their way,

Long line of carbines straining for the fray.

“March with me men!” they step, a roar

Of angry bullets fly,

Hitting the floor, splatter’d in gore,

Bullets graze Goering’s thigh,

While Hitler scamper’d safely off, & left good friends to die.

Munich

1923

Bolshevik Baton

After your death

It was windy every day

Every day

Anne Carson

Death shadow’d the legend-life of Lenin,

That ceaseless leader-slayer of the Tsar,

Wheel’d thro’ wet woods, slowly, by Joe Stalin,

Spoon-feeding poison’s ruthless coup de grace;

The man is dead,

But now the God is born,

Drap’d in the Russian red like rosy-finger’d Dawn.

As bonfires warm the freezing square,

Queues trail down every side-street,

Breath funnelling the sunless air,

Patiently wait to meet

A corpse embalm’d – the empire’s heir

Sentinel, stamping feet,

Stood guard o’er the focus of devotion –

Before him coasted a bear-fur ocean…

…To whom he gestures for silence,

Voice stylish, loud & clear

The arrogance, the violence,

The flashy Cavalier-

“We shall make Mother Russia great!” for “Stalin!” thousands cheer.

Moscow

January

1924

Mein Kampf

Everybody must roar his defiance.

Arise! Arise! Arise!

Millions of hearts with one mind

Tian Han

The world’s press finds the Blutenburgstrasse,

Beheld a new media sensation,

Some strange, enigmatic insurrector,

Shrieking, “I am the nation’s salvation!”

Thought’s purest prime

Hess summons to his room,

Dictating all the time his stately visions bloom.

“The Germans are the Master Race

& over the Earth shall lord,

We must secure our living space

Eastwards with a war-sharp sword,

Where Slavic chaff shall serve our grace

& Sanhedrim abhor’d

Be cut out like the cancer that they are…

Then build a global throne upon the scar!

…But first must come conflict’s dull pain;

The reckoning with France,

Then march to gain Russian champaigne,

Such fertile, vast expanse…”

A warbling lark left both entranced, watching the blossom dance.

Landsberg

June

1924

Busker’s Holiday

The more the autumn wind is wicked

And the moon desperate, —

The merrier we, vagrants, get

Georgiy Ivanov

The Putsch becomes a martyrs’ memory…

His wound well heal’d, tho’ each day morphine craves,

Herr Hitler’s plenipotentiary

To Venice travels, of the tender waves;

His wife beside,

In love to all appear,

As gently they did glide by tendant gondolier.

They took a train to meet, in Rome,

Il Duce’s iconoclast,

But heard, each hour, “he’s not at home,”

Such a dirge of days were pass’d

Round Roman tombs, St Peter’s dome,

‘Til realis’d, at last,

His mission, to acquire from Fascist friends,

Firm source of funds had fail’d… Herr Goering sends

A letter to Bavaria,

Which disappointment fills;

While, scarier, there’s barely a

Pfenning to pay the bills,

The Nazi squirearchy into obsoletion spills.

Prenestina

July

1924

Monty’s School

On the strength of one link in the cable

Dependeth the might of the chain;

Who knows when thou mayest be tested?

Captain Ronald Hopwood

As mortal mixtures of Earth’s many moulds

In substance vary – density & mass

& destiny, too, which Lachesis holds;

Those student soldiers, one afternoon class,

Sense something deep

Within their teacher’s soul,

Like greatness half asleep, behind time’s creeping wall.

“The soldiers art is pure details,

From the spotlessness of dress,

To knowing all his effort fails

If a moment of success

Unfollow’d up, triumph soon stales,

Inactions deem useless –

So, be incisive boys, whene’er you can,

& victory springs from the simplest plan!”

With common sense quite clarified,

His lads all loved to learn,

& bright applied each light their guide

Thro warfare’s fires did burn –

A luminary torch to whom with joy they yearn’d return.

Camberly

November

1924

Mussolini

more faithful man was never known,

and (from Valerius) we learn

that he was named the Great in Rome

Compiuta Donzella

As rivers gently drift along the glen,

Then gather speed & gallop down the falls,

New Ceasar, elevated by his men,

Has cross’d his Rubicon to take Rome’s walls;

Whose government

Made Fascist Mafia,

Whose Black-shirts implement a fresh brand of terror.

Ciano left the rush of Rome

To meet his lord & idol,

Strolling about his famous home

Beneath some crumbling castle,

Where playing in the sunswabb’d gloam,

A pretty, pig-tail’d girl,

“Signori, who is she?” “My eldest child.”

“Her name is?” “Edda, essentially wild!”

Il Duce donn’d his sleeping robe,

“My boy I must retire,”

Thick fingers probe the spinning globe,

Rest on his heart’s desire –

The little isle of Malta to attend his Black Empire.

Rocca Delle Caminale

1925

The Pilgrim

The altars burn,

And our voices soar

To God’s very throne

Anna Akhmatova

It was a day of thunder in the hills,

When Winifred beshook Herr Hitler’s hand!

Electric shock unblocks the pagan thrills,

He surely was the wonder of the land,

As Wagner was

When Nibelungen wrung

From primal minds because their spirit must be sung.

The orchestra did sooth & rage

To beautiful conduction,

Brunhild & Seigfreid gave the stage

A seminal production,

& then, when Wotan war did wage,

Valhalla’s destruction

Induc’d, in Hitler, total ecstasy,

That art for us, was for him prophecy.

She led him to the private tomb

Of the Wagner garden,

In moonlit gloom one could assume

Moods were tun’d by Hadyn,

As felt he brother demigod, Zeus, to this Poseidon.

Beyreuth

July 23rd

1925

Squadron-Leader Bligh

I’ll wait for daybreak

and we’ll figure out what to do

with all this sunshine

Harriet Anena

With skilful ease he piloted the plane,

Views zooming under albescent sky;

Thro’ patchwork carpet snakes the Bognor train,

‘Tween tenements of barley rusk & rye;

Swooping the Downs

Loops the stylish flyer,

Oercruising coastal towns, circling Chichester’s spire.

They heard his bi-plane’s buzzing speck,

Propellers eager spinning,

Wing him atop the field to check

If the Old Boys were winning;

He parks his steed, kisses Kate’s neck,

“Let me save the inning!”

“We need a six off the last ball to win!”

Giles Smythe-Tompkinson bowls a wicked spin;

With willow-flash the ball was sent

Beyond the bound’ry rims,

“Huzzahs!” are vent, into the tent

For sandwiches & pimms,

Says Nigel Bligh, “Back to the sky before the evening dims!”

Goodwood

1927

(AA) Canto 4: Fascist Dawn

Nuclear Pretensions

When or where did the ancient world, or ours,

Ever see such lively, ever feel such pure

Light coming out of dark ink

Giambattista Marino

Pools of academic alligators

Are jewels in the muddy earth of us,

Repudiating repudiators

With gliding minds, perfectly merciless;

What feats of brains

Did beastlike congregate

About the crystal chains, to conquer & create.

Now branded ‘Oppy’, broomstick thin,

A dashing, tall chain-smoker,

Who wanted everything to win

From bursaries to poker,

& after dark, cigars & gin,

Just a Joe Bloggs joker –

But all the time, relentless, without pause,

His brain was calculating Newton’s laws.

He chew’d, with Otto Hahn, the cud,

Cueing up the Meson,

The whole world could be won if would

Be conjur’d, with right reason,

Dropping bombs atomical the next time war’s in season.

Gottingen

1927

First Waves

My heart is drowning in love for you

I am so proud of you

I pledge my life to you

Sayed Khalifa

Little white cloud-flake breaks a blue spring sky,

While below, in the glittering city,

Sit avant garde sipping martini dry,

The men looking good, the women pretty;

Beneath that cloud

Defeat did, drifting, fade;

The people laughing loud at this strange street parade.

Men joining hands, chests out-puffing,

Herr Hitler & disciples;

Hawk-ey’d Hess, gorbellied Goering,

Club-footed, dwarfish Goebells,

Himmler completes the inner-ring,

Lord of the Schutzstaffels;

Defended by the brown-shirted SA,

Sensing their time will come… but not this day…

That will end in disappointment –

Like condescending water,

The party sent just three percent

From the common voter –

Who on earth would ever let a Nazi date his daughter!?

Berlin

May

1928

Dionysia

Ladies & young men in love,

Long live Bacchus & long live Love!

Let every one make music, dance, & sing

Lorenzo De’ Medici

Excess in Weimar’s capital prevails!

This eldorado of exquisite chic

Cocaine contains – characters & cocktails!

Round Adlon’s rooms swan-headed trollies creak,

Where julep mint

& complex oyster dish

Spice every ducal stint with a royal relish.

From cocktails at the Jockey Club,

They flooded to the negro bars

The jumbl’d, thumping, huddl’d hub

Where saxophones & guitars

Muffl’d the bass’s double dub

Where decadents from Mars

Surround the Carolina cryin’ queen,

Freaks cheek-to-cheek her plaintive wails did preen.

In saunter’d Roehm, a transvestite

Busty, in bright blonde wig,

& gave a light to some young sprite

Naked but for a fig

& took him to a secret room, men grunting like a pig!

Berlin

July

1929

Wall Street Crash

Tents of winds are my home

And stones are my furniture

The cycle of my days is one of curses and misery

Mustafa Seed Ahmed

Young land of a liquor-laced razzmatazz,

Grown richer from the Big War’s victory,

Home to the silver screen & jive-cat jazz,

Flag-waving for global prosperity;

Along Wall Street

Ford motorcades whizz by,

Whole Princeton, Yale compete for share-blocks rising high…

Whose dreams, in one black instant fell,

Auguring the global doom,

Strain’d faces yelling, “Sell! Sell! Sell!”

Burst the pink bubblegum boom,

‘Twas like some scene from Dante’s Hell

As chaos gript the room,

& thro it all one sharp sound to derange –

The staccato click of the Stock Exchange.

“All dem good times dey be over,”

Serfs cry from shore to shore,

How ruthless the great leveller,

Rich stoopeth with the Poor,

A wicked vortex currencies upsucking by the score.

New York

October 28th

1929

Nazi Fires

If I were fire, I would set the world aflame;

If I were wind, I would storm it;

If I were water, I would drown it

Cecco Angiolieri

The mountains seem’d in song, as fell the snow

On Oberstdorf; whose timber rooves did seem,

To all who gaz’d upon the streets below,

A darling face in a sensual dream;

Herr Dietrich lit

Saltpetre cigarette,

Continuing to sit, a hunter with a net.

The townsfolk all surpris’d to see

First physical swastika

On Dietrich’s arm, show sympathy

When, bullish as Boudicca,

He spews, “this world catastrophe

Jews of America

Have conjur’d – a dystopian nightmare,

With vermin infiltrating everywhere!”

With set of sun he rode the slopes

Up in a cable car,

By torchlight gropes around laid ropes

All smear’d with pitch & tar,

To light bewitching swastika – that flaming, far-seen star.

The Nebelhorn

November

1929

Der Fuhrer

Magnanimous Despair alone

Could show me so divine a thing

Where feeble hope could never have flown

Annamacharya

Max Stemmler took Kreuzberg’s mendicant streets,

Epiloguizing dejected fortune,

Each crashing bank long labour’s theft repeats,

Made money might as well be on the moon;

One grey stone wall

New poster burning bright,

Piercing his solemn soul as if ’twere holy light.

Max bought the party newspaper,

Absorb’d it over coffee,

The Voelkischer Beobachter,

Giddying philosophy,

Promises of doing better,

See… today… a rally!

He asks for the bill, “Danke, that was nice.”

“Since you’ve come in coffee doubl’d in price!”

A new Crusade to test the Jews,

None knows just what it is,

Pairs of worn shoes torn into twos,

Scuddle home in phrenzies,

Flogging that dogged gospel to bedraggl’d families.

Berlin

1930

Businessmen

Yea, the coneys are scared by the thud of hoofs,

And their white scuts flash at their vanishing heels,

And swallows abandon the hamlet-roofs.

Thomas Hardy

From Immenstadt & Kempton went the boys

So proud storm-troops to be for the SA,

A clank of jackboots, rhetoric & noise,

& over-barging all fools in their way;

Threw crude Jew jibes

At holidaymakers,

As when astonish’d tribesmen first view’d the Quakers.

Hoteliers from round the town

Congather’d, handshakes, all smiling,

‘Til with a stern, mood-slicing frown,

“Those bastards unbeguiling

That prance about in shirts of brown,

Paradise defiling,

Are scaring off our customers, you know,

I mean… Ringelmann, he is a maestro!”

“Judge Neuberger, a whole floor takes

All summer – each carafe

With wine & steaks adds up, & makes

Good wages for my staff –

The Jews are good for business – while the Nazis just make me laugh!

Oberstdorf

1930

Festival of Rice

He was adorned in his very best,

he was oiled like a king,

with beads of silver in his hair

Ama Ata Aidoo

As Basho join’d the chanting how he cuts

A handsome figure in those robes of gold,

Among the drummers round the paddy huts

With Kagarume dancers, young & old;

As wood blocks flail

To clank of bamboo rods,

The Sumiyoshi hail the Shinto harvest gods.

With dip & swirl the girls releas’d

The whirl of a spinning top,

The fields are bless’d as begs a priest

The boon of a fruitful crop,

then villagers all flock to feast

& drank dry every drop,

As did ancestors centuries ago

Intently sentimental went Basho

& toasted all the emperors

“Their names grow with the trees,

Who fend for us, descend for us

On Heaven’s splendid breeze –

To these I am devoted, & to all we Japanese.”

Kansai

June 14th

1930

(AA) Canto 5: Crescent & Cross

Islamica

Even the flowers greet you as of old;

Then you may well divine in what degree

My heart has already welcome for my friend

Kokin Shu

In pagan Mecca was man-mountain born,

Thro’ meditations in the Hiran cave,

From Heaven’s will Qu’ranic verses shorn,

But shunn’d from town with condescending wave;

Still, Medina,

His righteousness perceiv’d,

”Those who pray to Allah by Paradise reciev’d.”

While Meccanese rode to rid

The deserts of this ‘prophet,’

Defensive actions made valid

By visions of Mahomet,

For bloody decade far outdid

All rivals threat-by-threat,

& with an empire flowing far & wide

Islam’s first Imam, cleans’d, at Khaibar died.

Those men who tasted the divine

Holler up a sandstorm,

Drive Byzantine from Palestine,

Damascus made a home,

Then from the holy city all the papists whip to Rome.

Jerusalem

638

Monjoie!

his patronage maintains every poet group:

in his palace drinking is no dream

for his great thronging generous troops

Niall Mor

Great Charlemagne has claim’d the Frankish throne,

The Seat of Christ is his to long sustain,

His blows prodigious yonder Rhine & Rhone,

Brings empire bustling to his sapphire train;

Firm by his side

Valiant Count Roland,

First lion of the pride, Durendal in his hand.

Great Charlemagne a palm’s breadth drew

His sword, Joyeux, for glory,

Nobles from Normandy, Poitou,

Maine, Gascony, Picardie,

Tourain, Flanders, Guyeme, Anjou,

& pretty Brittany,

Traverse the ancyent vales of Ronceveaux,

Spain’s delitescent leagues searing below.

Such a battle is upon us,

Twyx Christian & Moor,

When beauteous Spanish passes

Turn wretched scenes of war,

When fell’d knights, decomposing, food for slugs & nuzzling boar.

Pyrenees

778

Crusaders

This desert, to which you came

with two raised palms like an absurd hope,

no longer begets prophets

Amjad Nasser

From the Praetendarius of Llanfair,

To the old Thesaurarius of Lille,

It seems Pope Urban’s essence moves thro’ air,

Prospering thro’ keen priesthoods, steeling zeal;

Christ’s foremost knight

Tours Europe’s fidget thrones,

“Those Muslims we must fight!” rouses convictive tones.

Men march & capture Antioch,

Long siege of land & water,

Fights infidels, from rock-by-rock,

Apocalyptic slaughter

Depleting, daily, human stock –

War’s terminal quota;

Infernal, body-mangl’d battlefield,

Where hymns mingl’d as the moaning for mercy peel’d.

From miracle to miracle

The city stood no chance,

A gritty yell, the citadel

To libbards, fell, of France,

Lungs bellowing, “Avanti!” “Adelante!” & “Advance!”

Jerusalem

1099

Sa-Lah-Din

It is bitter

To walk among strangers

When the strangers are in one’s own land

Iain Crichton Smith

The Crescent League cries faith & sacred war;

Turban’d Berbers, pitch-black Afric captains,

Pristine Emirs, the shark-paced Almacor,

Sunburn’d Saracens, fervent Syrians;

Lord at the helm,

One man unites them all,

To raze Outremer’s realm & seize the Wailing Wall.

Damascus & Aleppo fall

To the dark Mujahaddin,

Crushing Christian armies small

At that slaughter at Hattin,

“Allah!” the cause, “Allah!” the call,

“Allah! & we shall win!”

At last, on Heaven’s city look’d he down,

Where man-on-man press’d forwards for renown.

The situation sacrosanct

Beneath a saffron sky,

The Templars thank’d their lord, outflank’d,

They set themselves to die,

Preserve their place in Paradise & Allah’s hordes defy .

Jerusalem

1187

Constantinople’s Fall

‘Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!’ cries she

With silent lips. ‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free’

Emma Lazarus

As panting deer outpace the panther’s claws,

Then sleep where wolves oft meet in company,

The Ottoman clamps down his drooling jaws

Upon outposted Christianity;

Eighty thousand

Gore-grizzl’d warriors,

Encamp upon the sand soft kissing Bosphorous.

As cannons swallow gunpowder,

To spit out destructive balls,

Devil clamour ripples louder

From the beaches ‘neath the walls,

Scenes of sorry death enshroud her,

Byzantium,who falls –

Janissaries slaying the last Ceasar,

Crescent flags commanding Kerkoporta.

Leaving the Sultan to his prize

The Genoese flee,

As local wise men realize

Passage to Italy,

They leave behind a changing name, shaming its history!

Istanbul

1453

Death of Chivalry

Her tears of bitterness are shed: when first

He had put on the livery of blood,

She wept him dead to her

Robert Southey

Beneath the Pyramids the Sultan stands,

Protecting ancestral lands Islamic

From Ottoman conquest, his line expands,

Across the sands, strange musket chambers click;

Fathomless force

That is the flow of time,

Electrifies his horseman on a charge sublime.

Bravebreast Aegyptians went to work,

Yanking drawstrings back on bows,

Deep lust for bloodshed bleeds bezerk

As fans one thousand arrows,

But images of future lurk

From the Turkish shadows,

Masters of black gunpowder blasting shots,

Withers the Mamluk line to trembling trots.

As Lion Kings must lose their pride

When old worlds meets the young,

Lead-ball-wall-wide of genocide,

Dead men from dead mounts flung,

As, knowing he would be the last, the last Sultan was hung.

Cairo

1517

Siege of Vienna

The bird in me awoke again

Its cry spread anguish

In the heart of my kingdom

Nimrod Bena Djangrang

Islamic spectres on Austria fell,

Vienna must, for Europe’s soul, stand firm,

Else Pasha & the Turkish infidel

Into the west & thro’ their wives shall worm;

Aiming the guns

At Allah’s grand empire,

More bonfires than are suns, the Kahlenburg’s on fire.

As constant as those perfect waves

That roll into Biaritz,

The Sipahi slip to their graves

In the death-deep city pits,

Tho’ conquest human honour craves,

At these extreme limits,

Facing superior technology,

The apex fled of Turkish history.

The royal horses are preserv’d,

Churches Hosanna sing,

Islam unnerv’d, Europe preserv’d,

Her internecine spring,

When bleeding for one’s empire breeds purpose in existing.

Vienna

1688

Gallipoli

They seek to bring us under

But England lives, & still will live –

For we’ll crush the despot under

Alfred Tennyson

Kitchener’s Churchillian conjecture

Battle brings before Constantinople,

Champagne thrill of Achaean adventure,

The Gentle, savage; the Savage, gentle;

“Where are you from?”

“Melbourne…” “Why are you here?”

Senses of soldiers numb, led captive to the rear.

The soul of Rupert Brooke releas’d,

Packs poetry for the trip,

Byronic sortie to the East

But mosquito punctures lip,

By volumes his visions increas’d,

Death climbs aboard the ship,

For what seem’d a tayle, epic & Trojan,

Now slowly sluiced with tragical poison.

From sandy cliffs to hills jagged

Sloping from Chunuk Blair,

Up ridge ragged, long trail hagger’d,

Thro’ hot, wilderness air,

Bluce Slater from Australia spat bullets ev’rywhere.

Turkey

August

1915

Ottoman Winter

Now stoops the sun, & dies day’s cheerful light.

When stars stread forth, intone this two-tongued folk,

Standing with firebrands, hymns of sacrifice

C.M. Doughty

Empires are born as glass is born of sand

Then turn to sand, scarlet sands Syrian

Are roam’d by one born of another land,

Laird of the head-dress’d horsemen of Hejan;

Fair Lawrence leads

King Feisal’s cavalry

Upon fine, strong-thigh’d steeds behind an enemy.

Thro’ olive grove & fields of grain

Wind the streets of Megiddo

Blows bloody fall as stormswept rain,

White the hot-edged sabres glow

As dim-spawn’d devils deal in pain

Angels honours bestow,

As thro the battleground of the furies

Tread the Fates with JUSTICE & her juries.

As was murder’d Montezuma

& Visigoths did ford,

Em’rald Tiber, from Syria

By Lionhearted sword

The Turks are toss’d accosted from possessions lost abroad.

Arabia

October 1st

1918

(AA) Canto 6: Swastikas

Omar Mukhtar

They are inevitably destroyed

Like plaster washed off in the rains

Like the sandy bank of a river

Lalitavistara

On Turkish carcass Italy doth gorge,

Only the true Senussi Rome withstood,

But tanks emitting from the Fiat forge

& gangs of fascists fill black pails with blood;

Closing a ring

Round Jebel Akhdar’s hills,

Where Muhktar’s rebel spring resistant moods instils.

As mustard gas, like falling snow,

Deals death & devastation

Il Duce on the radio

Thro’ camps of concentration,

the struggle crumbles blow-by-blow –

To ensure starvation,

At Egypt’s border wire divides the sand,

& every mosque as clos’d down out of hand.

At last the Desert Lion caught,

Treasonly convicted,

The noose grew taut, a life cut short,

Watchers on predicted

The Goddess KARMA could no let such acts go unafflicted.

Suluq

Libya

1932

A Sudden Engagement

A gentle wind fans the calm night:

A bright moon shines on the high tower.

A voice whispers, but no one answers when I call

Fu Hsuan

“Costanzo, Granduca di Livorno,

This nouveaux Fascistnoblesse has a son

Handsome enough, his name Galeazo…”

Whom Edda meets, tho’ neither is smitten

A film-date shar’d,

Topless girls pearl fishing

In Polynesia, staring silently, wishing

The bodyguards a row behind

Would vanish on their vespas,

This role she lived lived all undefin’d

Where suffocation prospers,

Her young man seems to read her mind,

Leans across & whispers,

“Do you want to marry me?” Edda smil’d

& said, “Why not?” – “My daughter, she is wild,”

Her mother said, “but one to tame,

A maschiaccio –

But, all the same, to her a game

This life – she shall not sew

Or cook – but be assur’d her love & loyalty will grow.”

Rome

January

1932

Deutschland Sings!

The two-voiced mouth of secrets shared,

We two make a single Sphinx.

The two arms of a single cross

Vyacheslav Ivanovich Ivanov

From boist’rous lieder of the Alpine south

To bawdy ballads of the Baltic ports,

Teutonic spirit, drawn first as a thought,

Emerges as music from every mouth;

Orchestras play

In Cafes, without pause,

The stage hits of the day to sing-a-long applause.

As over wooden balconies

The housemaid hangs a mattress,

She fills the air with melodies –

Clad in well-iron’d hiker’s dress

Stroll the strumming mandolinnys

Along lanes litterless

Thro’ the old walls to the forest hills,

While to those women at the window sills

The boatman from his flowing throne

Waggles happy fingers –

The scratchy drone of gramophone

Cast the meistersingers

Around the square ’til overwhelm’d by the handbell ringers.

Heidelberg

1932

Fascist Nuptials

We think we know ourselves, but all we know

Is: love surprises us. It’s like when sunlight flings

A sudden shaft that lights up glamorous the rain

Liz Lochhead

Explosions of fragrant fecundity

From azaleas, roses, gardens fill,

Spill’d from Torlonian villa, pretty

Edda look’d, like a tower on a hill,

Or Dante’s muse,

The wedding party march’d

To San Guiseppe’s pews thro’ gladiusi arch’d.

As Papal Nuncio demands

The day to be religious,

Ambassadors from many lands

& editors prestigious,

With uniforms, bejewell’d hands,

Diamonds, furs, prodigious;

Surround the darling dance of vows & rings,

That consummates recurring terms of kings.

Choir singing Romagnolan hymns,

The bride & gloom set free

To lock lithe limbs, their fiat skims

The vias speedily

To Hotel Quisisana on the island of Capri.

Rome

April 30th

1932

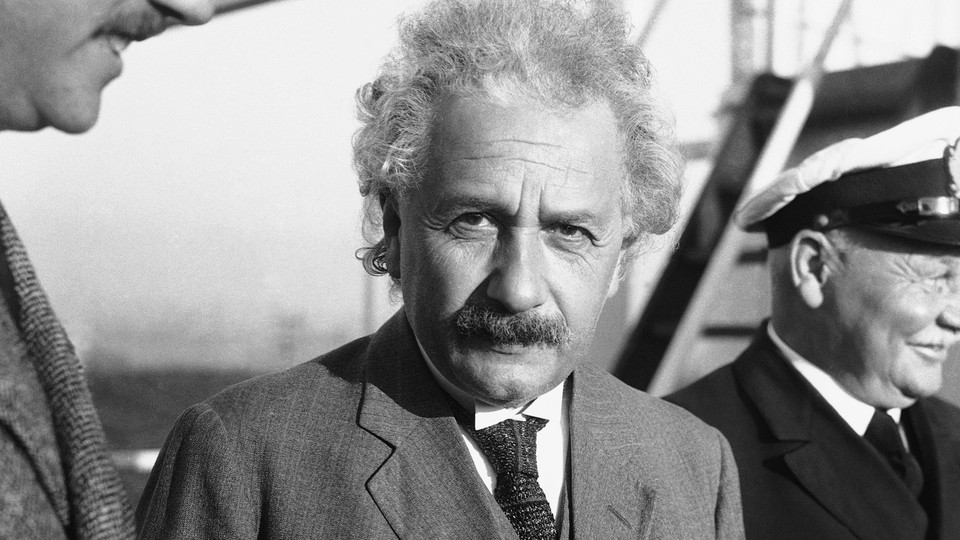

Albert Einstein

Prisoners of hope, arise,

& see your Lord appear !

Lo ! on the wings of love He flies

C Wesley

This crazy prophet, this quantum guru,

Destroys Man’s mute concepts of time & space,

Whose mind alert enough to feel the Jew

Must face the fury of the Master Race;

If in their hands,

They had the bomb as well,

The world shall understand naught but ‘Gott in Himmel!’

Heart-skipping to the mercedes,

Arm-hugging his Yankee guest,

Mouth-speaking amidst garden trees

Of the e’er enticing West,

When wistfully Albert agrees

To leave the nuptual nest…

“When?” he furrows his Newtonian brow,

Kisses his darling wife & whispers, “now!”

With liquid eyes & drought-dry throat

One most emotive day,

Thoughts all afloat he boards a boat

Bound for the USA,

Those realms of milk & honeydew, three thousand miles away.

Antwerp

November

1932

Yin & Yang

My strength is the strength

Of ten young things: I am with you:

In that first moment of delight

Roethke

Oer Berchtesgaden Ribbentrop arriv’d,

Found Hitler waiting at the Wachenfeld,

In whom the simplest of solutions thriv’d

Express’d in simplest terms – the two just gell’d –

The Nouveaux Riche,

The Circus of the Brawls,

Stitch’d in a sick pastiche – &, as evening falls,

It ends with an invitation,

“Do visit us in Dahlem…”

‘Twas a mental liberation

When he left the ‘Us’ for ‘Them’,

Cultivated conversation

Off-syphon’d caustic phlegm,

As Ribbentrop did ably demonstrate

The table manners of a man of state.

Ammelies was quite delighted

To meet her husband’s guest;

Who converted, nay, devoted,

Upon his wife impress’d

Herr Hitler was the antidote to Deutschland dispossess’d!

Berlin

1932

Breath of Evil

I chewed all my dreams

In the fragile bowls

Of our independences

Charles Ngande

Freya Von Moltke ador’d her husband

As Germany his famous ancestor,

A soul conceptually enlighten’d,

Quite unlike this fright’ning man before her;

Wild animals

Surround him in a pack,

As cinematix swells, breath burns into her back.

Beside a sibbilantine blaze

Stood the district magistrate,

Helmuth onlisten’d with amaze

“Leave the Nazis to their fate

Let inefficience stem their craze,”

Splurts Helmuth, “they’ll create

Dystopian catastrophes of doom!”

In burst his wife, like panic, to the room.

“I saw him in the cinema,”

“Saw whom?” “Herr Hitler!” “Him!”

“Our eyes did spar, his dreadful tar

Did coat unquiet, grim,

Dim orbs as dull as stormclouds after sunset on the rim.”

Berlin

January

1933

Chancellor Hitler

Opposite them a peculiar fight

enables the drinkers to lay aside

their comic books and watch with interest

Al Purdy

The old ones in the Reichstag share their fears,

Kabbalic nest of arch-intiguerie,

The Nazis know their day of glory nears,

But not quite yet, no clear majority;

Arms magnate meet,

“That man most warlike seems…”

“Aye, let us fund his feet, & permeate his dreams.”

Charming all the right-wing parties,

‘The front of the Harzburger,’

Plus money from the industries

& Mussolini’s lira,

All of Germany criss-crosses,

Rallying each burgher,

On every side the SA’s numbers swell,

‘Tis better than the jobless carousel.

Soon into power Hitler sworn,

His cause célèbre won,

Tho’ wintry morn chills to the bone,

He seems a shining sun,

Some prophet like Ezekiel, God with a gatling gun.

Berlin

January

1933

Unter Den Linten

The zealot’s flame deep in the hot brown eyes

That glowed with strange and holy whisperings,

And searched the stars, and caught angelic wings

Alan Sullivan

Hitler breakfasts by the Wilhemstrasse,

Freshly elected Chancellor to be,

When possessing Berlin controls Prussia,

& those controlling Prussia, Germany!

Beside the flag,

Luddendorf whispers, “This

Accursed man must drag us all down the abyss!“

Men drank until the sunset made

A berth for the Evening Star,

Forming a happy cavalcade

Beneath Brandenburger bar,

As if with Bismark to parade

The Kaiser’s spoils of war;

Into the city, under the lime trees,

Ribbons of torchflame flicker’d in the breeze.

“Seig heil! Seig heil! Seig heil! Seig heil!”

Der Fuhrer close to tears,

His stoneface veil torn by love’s gale,

Arms jerk up to the cheers,

“We must build up a Reichland to endure ten hundred years!”

Berlin

January

1933

(AA) Canto 7: Ravenswarm

Imperial Hypocrisy

At noon in the desert a panting lizard

waited for history, its elbows tense,

watching the curve of a particular road

William Stafford

The Japanese drop bombs upon Shanghai,

The flooding blood of innocence is shed,

The League see a glint in their slinty-eyed

Members, summon’d to answer for it’s dead;

The crux has come

When empires young & old

Shall totter up the sum of all their stolen gold.

The bespectacl’d Yosuke

Rails the Trans-Siberian

Thro’ Moscow’s hospitality

To the shores of Lake Lucerne,

Hectors crumbing fraternity,

“Who shall cast that first stone?

To civilise China good soldiers died

But condemn’d here as Christ was crucified!”

Cast was the ostracizing vote,

Yosuke disinclin’d

Donn’d his dark coat, & clear’d his coat

“We terminate this bind!”

Scrunch-scrapp’d up piece of paper, left the world bestunn’d behind.

Geneva

February

1933

Pilgrimage

Age & decrepitude can have no terrors for me

Loss & vicissitude cannot appal me

Not even death can dismay me

Elizabeth Hayson

A holiday to feel alive & free,

To visit the Communist templeground

Anatoly ushers his family

Onto the train for Moscow Central bound;

As Russia spread

Forever, seemingly,

Their borodinsky bread graz’d, gazing dreamingly.

In the wake of private enterprise,

Cos there aint no I in team,

Utopia the common prize,

As their statehood reigns supreme,

the towers of the kremlin rise,

Some magic mythomeme,

But, cold & bleak, the cobblestones speak drear

As like a winter’s mist, all sides, hangs fear.

“Is that him, father?” “Yes Sergei –

Dosia! Konstantin!

Come see…” some sigh, some groan, some cry,

Some let the angels in,

Gazing at the glorious immortal leader, Lenin.

Moscow

1933

Anti-Semitism

An unhappy, evil nation

Treats its victim’s self-oblation

In unworthy fashion

Adam of St. Victor

At the heart of European Jewry,

Fair city of the Rotheschilde’s high finance,

Miff’d Moses Grunfeld dismiss’d from duty,

His former friends purpling with arrogance;

A hiss, a jeer,

“Go scum, go spread the news,

Your kind will not work here, you & your filthy Jews.”

He walk’d (they forced him from the tram)

Into the Jewish boycott,

His heckles up, hands all a-clam,

Some cassirean gauntlet,

Trying to purchase bread & jam

Abuse was all he got;

Up oer orizon swept a storm of tears,

He went to sit with father & his fears.

Gone mournful thro’ the cemet’ry

Between the Jewish graves,

On bended knee, in misery,

Tears streaming down in waves,

His parents’ tomb some spiteful, scarlet hakenkreuz enslaves.

Frankfurt

1934

A New Dictator

with apologies for the inconvenience,

they carefully wrapped barbed wire

round the wrists of the political prisoners

Frank Chipasula

On the dreaded Sturmabteilung men point

Black pistols to their brains, the triggers pull

& spray their brains out wallwards to anoint

The National Revolution from the skull;

That list of doom

Was tick’d off name-by-name,

For these there was no room in Hitler’s grander game,

Where stands he all supreme, the lone

Arbitist of Germany,

Commanding legions from his throne

With a frantic fealty,

Right arms rais’d high they’ll set in stone

Most precious loyalty –

“We swear obedience by holy God,”

Der Fuhrer took each promise nod-by-nod

& christens himself ‘Grand Marshalle’

Lord of all the forces;

Of shot & shell, Alf Nobel’s gel,

Uniforms, field horses,

Tanks, planes, U-Boats, mine-fields, E-boats, fortresses & soldiers.

The Third Reich

August

1934

Death of Anatoly Stiltski

Va! meurs! la derniere heure est le dernier degre.

Pars, aigle, tu vas voir des gouffres a ton gre;

Tu vas sentir le vent sinsitre de la cime.

Victor Hugo

As Phoebus prick’d the dusty harvest haze,

Stalin’s lapdogs surrounded quaint Moshny,

Amid this bastion of the old ways,

Anatoly fear’d for his family;

Ring of cold steel

His wee home’s scape-proof mesh,

Machine-gun muzzles wheel & lacerate his flesh.

While wife & daughter wail & gnash,

His sons weep & thrash in vain,

All toss’d aside like filthy trash,

‘Brethren’ burning long-grown grain…

By slaughter’d cow, like human rash

They stagger’d thro Ukraine

To this city of cold, modern concrete,

Where hunch’d, hungry man-shadows stalk the street.

While pondering in pity’s square

Her kids beg with a song,

Old merchant’s stare soothes their despair,

“Your boys look fit & strong –

Come work for me!” her family timidly tag along.

Kiev

1934

Gleichschaltung

Doth someone say that there be gods above

there are not; no, there are not. Let no fool,

Led by the old false fable, thus deceive you

Euripedes

The scent of sweat & leather wets the air

Certain men stood silent; gazing sadly

At swastikas demanding everywhere

Mental attention glamourised madly;

Children shatter

Eardrums of all they meet,

Shrieking out, “Heil Hitler!” to narcotize the street.

In the grip of exultation,

From the forests’ ancient roots,

Watch the old gods reawaken

Thro’ crude staccato salutes;

Jesus Christ has been forsaken

& all his angels’ lutes –

The tribes are rising, formally reborn,

Whose supreme chief the dragonsteeth hath sewn.

“The Bolsheviks, Novgorod’s bear

Must by us halted be!”

Defending their primeval lair

A race collectively

Embracing Hitler’s righteous cause have set the wyvern free.

Germany

1934

Dictators

The Chancellor met his flashy idol,

Most dashing in medals, fez & dagger,

Together tour’d the stunning Grand Canal

Whose conversation in a gondola

Passes under

The famous Bridge of Sighs,

Where men watch with wonder & glory in their eyes!

Benito speaks, in Adolf’s tongue,

& spirit, of alliance;

“Let’s carve ourselves, before too long,

Spheres of Fascist influence

Together, then, & friends, & strong,

Great Britain test, & France –

& if the world would ever come to war

Let our bold Axis pierce the planet’s core!”

Der Fuhrer’s turn, Il Duce bored,

As monologuing long,

Hitler outpour’d, from spittle gourd,

A game of great Mahjong,

Fearless of steering gondoliers into a billabong!

Venice

June

1934

Prosperity

Not in the clamour of the crowded street

Not in the shouts & plaudits of the throng

But in ourselves are triumph & defeat

Henry Longfellow

Herr Stemmler clock’d off from the factory,

Proud to collect another working wage,

By S-Bahn trundles thro’ this great city

Sunk deep into Mein Kampf’s numinous page;

Sacraliz’d tome

Of Germany reborn,

Preaching in town & home under a crown of thorn.

Max buys a clutch of books & toys,

Then sprints off home for dinner

Gives out the gifts to his glad boys

& pale autistic, daughter,

His wife turns up the wireless noise

Belching propaganda –

Stealthily increasing by decibels

Minds being poison’d slowly by Goebells.

They went out to the silver screen

To gaze on holy face,

Whose angel sheen, strong yet serene,

Shone blithe & full of grace

Berlin

August

1934

Oaths of Loyalty

It grieves me that thy mild and gentle mind

Those ample virtues which it did inherit,

Has lost. Once thou didst loathe the multitude

Guido Cavalcanti

Heavenly Vale of Operatic Hearts,

Hemm’d in by behemoths huge, hewn from stone,

Those cool, majestic mountains of the Harz,

Witness a soldier of the Aesir born;

An eagle flings

His wings to airy dawn,

As ev’ry treetop sings for chandelier’d dawn.

On receiving the Reich leader

He dismiss’d der Fuhrergaurd,

Offers men of the Third Jager,

Lords of La Haye Saint’s courtyard,

“I have made my men a soldier

Enough to hold Asgard!”

Appeal made to militarizing creed,

Not hopeful gesture… but resolute deed.

Awe trembles as his soul’s captain

The Honour Guard inspects,

Hitler has won his devotion,

Aft’ solemn oath extracts,

His ear is pinch’d & in that instant Rommel’s all accepts.

Goslar

1934

(AA): Canto 8: Resurgences

A Daring Stroke

Well done! You have conquered anger!

Well done! You have Vanquish’d pride

Well done! You have banished delusion

Uttaradhyana Sutra

Schact strode down the bustling Wilhelmstrasse,

Admires the grandiose Reichchancell’ry,

Usher’d to the office of his Fuhrer,

“Have you used your license to print money?

Across the land

We’ll re-arm clandenstine!

“This is what I want & this is what must be mine!”

With spirit assertive as steel,

He silences the Reichstag,

“I have the honour to reveal,

That under the party flag

Our soldiers march with strength & zeal

To slay the scallywag

Of our Rhineland’s criminal occupation, –

Confident of global approbation

Stream across the Rhine tonight

Goosestepping with such pride,”

& he was right, no appetite

For conflict clarified

His keen assessment of the Entente Cordiale’s divide.

Cologne

March 7th

1936

The New Rome

He sins and drinks and gambles

and in a backwards twist of luck

she suffers, fights, and prays

Adela Zamudio

Clutching crude spears & shields of Rhino hide,

Brave tassle-beards defend these lands once free,

Tho’ overhead planes glide cross countryside

Spitting caustic droplets without mercy;

As lethal mist

Poisons their thirsty land,

The will to still resist erodes to sinking sand.

As shadows of Mount Antoto

Drew long over Ababba,

A last, hot flash of bullets flow

From their fearless Emporer,

Chok’d on the hopeless word to go…

Then hail the conqueror,

When Mussolini’s legions, triumphant,

Banish the anguish of late Rome’s lament.

“My good people are suffering!”

Tears stain’d Selasso’s eye,

Altho’ the king stands soul-weeping,

The League hangs idly by…

Men melting into mountains underneath a bomber sky.

Abyssinia

March

1935

Transformations

As a clear crystal assumes

The colour of another object

So the jewel of the mind is coloured

Aryadeva

The mutilation of the soul begins

From burning books the past is falsified,

For those who sway the mind the spirit wins,

& those who smite their protest must have died;

Such whispers swell

About the foul regime

When in the torture cell no-one can hear you screanm

Goebells insists a wireless set

Like the cross hung in all homes

As when the Christian was yet

Untouch’d by the serpents tongue,

As propaganda cast its net

On minds of old & young,

Grasping at Hitler’s visionary bliss

All of life’s aspects lick’d by lizards kiss.

Society dissolves, reform

By swastikan twin snakes

That grip & swarm – the tannenbaum

Fair angel tip forsakes,

For this is Earth & alters things thro’ tectonic earthquakes!

Germany

April

1935

Hitler Youth

I have thrown way the veil,

I have taken refuge in the great guru

& snapped my fingers at the consequences

Mirabai

Max Stemmler roars along the autobahn,

Palingenetic tribute to contree,

Musing upon the Battle of the Marne,

So close to Paris, & to victory!

He parks the car,

Bear-hugs his eldest son,

“My boy if we must war, with you our battles won.”

Khan dined with peers clever & couth

As his malleable mind

Bombarded was with Nazi truth,

The majesty of their kind,

Carefree below the starry roof

Boys talk’d & laugh’d & dined,

Singing proud songs, so strong & beautiful,

Of Lebensraum & of love of battle!

They run, they swim, they fight, they share

The life of Herr Soldier,

As mountain air rang with fanfare,

They planted Swastika

On summits for the glorious Fatherland & Fuhrer.

Harz Mountains

1935

Fascist March

Crumbled I die

Tortured I die

In innocence

Albert Kalimbakatha

Sensing a most depress’d & restless Rome,

If Rome, of course, the whole of Italy,

Turning the focus from his forehead’s dome

T’wards paths of hypnagogical glory;

Enseismic shift

Rumbles athwart Mankind,

His anchor rais’d as drift the lamarckians, blind.

From Erit & Somalia

Marches facinorous creed,

Oer ancyent Abyssinia

Like some martial millipede,

All the churches rang in Pisa

To celebrate the deed,

Of conquerors, their brave & bouyant band,

Gone marching, all, into the promis’d land.

Men thee hail, Haile Selassie!

As Emperor, as King,

The grand Gabbi sends Italy

A message, as they sing,

“Repulse, resist, punish, persist, them from our farmsteads fling!”

Addis Abbaba

October

1935

Nazifizierung

They will soar on wings like eagles

They will run & not grow weary

They will walk & not be faint

Isaiah

The Battle of the Jobs Front has begun,

Infused the words, “work sacrifice” thro’ all,

While conscripts for rural conservation

Cry ‘blut & boden’ as their warring call;

Militariz’d,

The language of the state

Hath deftly appetis’d the Holy Knights innate.

As blue-ey’d girls in bows & rows

Learn vigour thro’ gymnastics,

& pirouette on tippy-ties

Or flex like stretch elastic,

Group leader peers along her nose,

Scribbling beside neat ticks

When itemizing all the better wombs

A visionary dynasty illumes.

The classroom fills, the leiter stands,

None dare there to tarry,

Question demands a show of hands,

Answers wee Hemirih,