The Pendragon Papers (6): The Architecture of the Epic

The idea for this paper came to me on a gloriously sunny January day in 2023. The peaks of Arran were skiffing with snow, & the sky rang’d eternally in a bright & vivid blue, pierc’d only by single clouds floating like zeppelins towards Kintyre. As I walk’d over the tops from Brodick to Lamlash, the idea that Shakespeare was also an epic poet of sorts really solidified in my mind, & the rest of this paper soon follow’d.

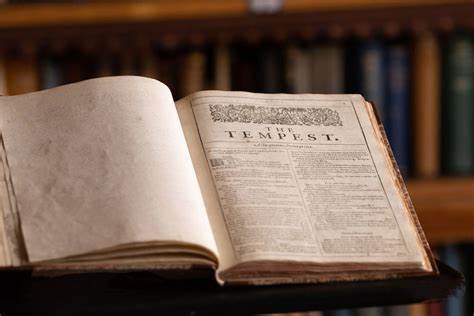

Poetry is a spiritual being that exists, is immortal even, & whatever that spirit actually is, it does take recognizable forms, Every now & again, I mean we’re talking huge swathes of time, its manifestation as an epic poem is its true & supreme expression. ‘What has been, may be again,’ wrote John Dryden, ‘another Homer, and another Virgil may possibly arise from those very Causes which produc’d the first.’ In the creation of these new epics, which Dryden also calls ‘certainly the greatest Work of Human Nature,’ it is undeniable that the burgeoning corpus will always draws upon traditions of the past. What many don’t quite understand either, is that the First Folio of William Shakespeare is also an epic, but not in the classical sense. However, once we see how in those 36 plays we cover the full gamut of Human experience & emotion, just as did Dante & Homer in their greatest productions, & when we realise that the national Tudor epic of England is embedded in the history plays, & that the entirety of the Folio is fill’d with scintillating poetical wordplay, drama, history, comedy, tragedy & all the interjoining complexities of the world organism, then it is easier to envision the Folio as an epic. In his essay ‘On the Progress of Satire,’ John Dryden intimates such thinking when he writes of native genius which, ‘were to Shakespear; and for ought I know to Homer; in either of whom we find all Arts and Sciences, all Moral and Natural Philosophy, without knowing that they ever Study’d them.’

Another clue is the number 36, divisible by 12, just as were Homer’s twenty-four books. To this bracket we can add Virgil’s & Milton’s twelve book epics, from which we are beginning to get a real sense of how the spirit of poetry is dictating to us that just as there are twelve months in the year, twelve star-signs, & twelve Chinese astrological years, etc., so twelve, or groups of twelve, is the number of books in which an epic most be divided. With one exception, that is, which is the 100 cantos of the Dantean epic, which he neatly divided into three books fill’d with 33 cantos, after the supposed age of Jesus at the Crucifixion. These 99 cantos are then preceded by an introductory canto, bringing the total to 100.

Before continuing, let us for a moment look at the description of the classical epic, by modern-day exponent, Nicholas Hagger, which he defined in the Preface to the first-edition books 1 and 2 of Overlord (1995) and quoted in a letter to John Weston in his Selected Letters, pp.547–548:

An epic poem’s subject matter includes familiar and traditional material drawn from history and widely known in popular culture, which reflects the civilisation that threw it up. Its theme has a historical, national, religious or legendary significance. It narrates continuously the heroic achievements of a distinguished historical, national or legendary hero or heroes at greater length than the heroic lay, and describes an important national enterprise in more realistic terms than fantastic medieval Arthurian (Grail) romance; it gives an overwhelming impression of nobility as heroes take part in an enterprise that is larger and more important than themselves. Its long narrative is characterized by its sheer size and weight; it includes several strands, and has largeness of concept. It treats one great complex action in heroic proportions and in an elevated style and tone. It has unity of action, which begins in the middle (“in medias res”, to use Horace’s phrase). The scope of its geographical setting is extensive, perhaps cosmic; its sweep is panoramic, and it uses heroic battle and extended journeying. The scale of the action is gigantic; it deals with good and evil on a huge scale. Consequently, its hero and main characters have great moral stature. It involves supernatural or religious beings in the action, and includes prophecy and the underworld. It has its own conventions; for example, it lists ships and genealogies, and the exploits that surround individual weapons. Its language is universally accessible, and includes ornamental similes and recurrent epithets. It uses exact metre (hexameters or the pentameters of blank verse). It has its own cosmology, and explains the ordering of the universe.

An epic poem essentially synthesizes the religious, philosophical, political and scientific ideas of an age into an integrated vision of the poet’s own belief systems, & that of their respective cultures. In the year 2023, we can count, then, six supreme models of the form. We have Shakespeare’s First Folio, Homer’s two epics, Virgil’s Aeneid – which is in essence the Iliad & the odyssey segued together, we have Milton’s Paradise Lost & we have Dante’s Divine Comedy. They are the supreme epic models, which are divided into groups that, in the spirit of botany, for poems are indeed the flowers of a plant, I have given Latin names.

Epicus Gracilis (slender, or Roman, epic): 12 books

The Aenied: Virgil

Paradise Lost: John Milton

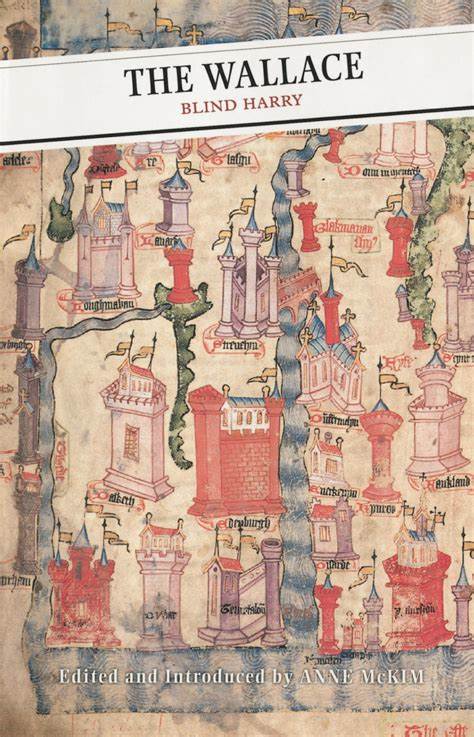

Other ‘Roman’ epics include the 11,877 stanzas of the Scottish epic, Blind Harry’s ‘Wallace’, compos’d in the late 15th century. It can also be said the Wordsworth’s fourteen book Prelude was naturally straining to become an epicus gracilis, but Wordsworth couldn’t quite tame the wild Pegasus, so to speak. For example, there are three cantos describing his residence in France, & two entitl’d ‘Imagination & Taste, How Impair’d & Restor’d,’ all of which could have been trimm’d down. Then, in the modern era, Nicholas Hagger compos’d the 41,000 line ‘Overlord’ epic, describing the final days of World War Two.

Folio Gracilis (slender folio): 12 plays

N/A

Epicus Grandis (larger, or Greek, epic): 24 books

The Iliad: Homer

The Odyssey: Homer

Folio Grandis (large folio): 24 Plays

The Conchordia Folio: Damo

Epicus Majestas (greater, or Dantean, epic): 100 Cantos

The Divine Comedy: Dante

Axis & Allies: Damo

Folio Majestas (greater, or Shakespearean, Folio): 36 plays

Shakespeare’s First Folio

I have included two of my own texts in the above lists. Axis & Allies is my principal epic, whose 100 canto are divided into 3 books of 32 cantos; preceded, divided by, & follow’d by four more cantos, bringing the total to 100. My Conchordia Folio, consists of 24 plays, which are then divided into subgroups, rather like the Odyssey is divided into 2 halves & also into 6 groups of cantos. For architectural interest I shall show here what I have been up to.

A quarter of the plays consist of my contemporary period Leithology sexology, whose dialogue is that of the normal unmeter’d speech of everyday human conduct. There are also two late twentieth-century set trilogies, both compos’d in dramatic blank verse, being Madchester & The Gods of the Ring, tho’ the second part of the Madchester trilogy is more of a rock opera. There is then a group of four conchords whose dialogue comes to us in the form of the modern Chaunt Royale, a Provencal troubadour creation which consists of five ten-line stanzas, completed by a five-line envoi. Of these, Stars & Stripes, & The Siege of Gozo, are purely Chaunt Royale, while Charlie &, finally, the Savoyards, also include elements of unmeter’d speech. We then have a group of four historical conchords all of which are purely in dramatic blank verse, being Viriathus, Atahualpa, the Flight of the White Eagles, & finally, Malmaison. The last group of four conchords are purely in umeter’d speech, being Gaston Dominici, Bela & the Brownies, Exes & Axes, & finally, In A Man’s Garden.

So much for my personal endeavours, but what about the epics that don’t quite fit into this scheme. Well, Spenser was attempting an Epicus Gracilis with his Faerie Queene, which he, ‘disposed into twelve books fashioning 12 moral virtues.’ He manag’d to get six & a half books in before putting it down forever. Another unfinish’d English epic poem is Byron’s Don Juan, which he put down 16 cantos into his plann’d 24. What we learn from this, then, is that to be truly consider’d an epic poet, one must first at least finish one’s epic poem.

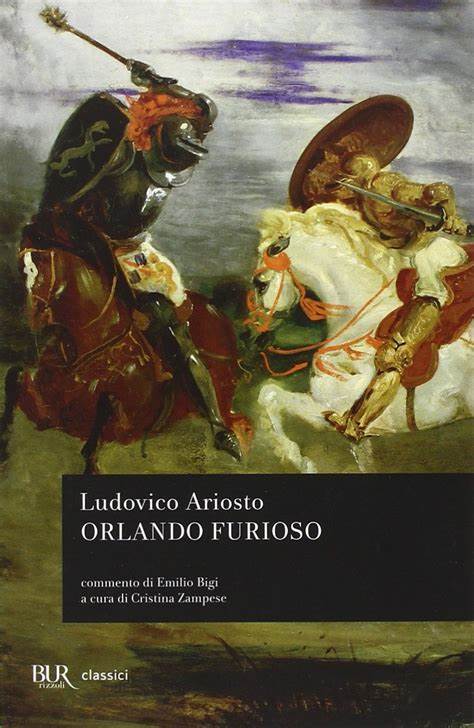

None of the Renaissance epics can be admissable into tthis paper’s lurch for form. Matteo Boiardo’s ‘Orlando Immarato’, consisited of 68 cantos and a half; Alonso de Ercilla’s ‘La Acaucana’ was 37 cantos; Ariosto’s Orlando Furiosa was 46 cantos, Tasso’s ‘Gerusalem Liberate’ was 20 cantis, & the Lusiads of Luis Vaz de Camoes contain’d ten cantos. But this period of experimentation was half a millennium ago, & follow’d soon after by Spenser at least attempting twelve cantos, & Milton similarly settling on the number twelve for Paradise Lost. There is comfort in structure, & just as a sonnet has fourteen lines, then let our future epics be moulded by the tenets contain’d in this paper, which is only a clarification of what several millennia of poetry straining to take on the form of epic, has taught us.

And long may it continue…

17/03/23