An Interview with David Kinloch

Hello David, so where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

Hello David, so where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

I was born and brought up in Glasgow, went to Glasgow University where I studied English and French then went down to Oxford where I wrote a D.Phil on an obscure 18th century Frenchman. During my time as a graduate student in Oxford I also worked for a year teaching English in Paris. Since then I’ve worked in a variety of Universities including Swansea and Salford. And since 1990 I’ve been back in Glasgow teaching first French and now Creative Writing at the University of Strathclyde. I live with my partner, Eric, in Mount Florida near ‘the home of Scottish football’.

When did you first realise you were a poet?

My grandfather was the Scottish poet, William Jeffrey (1898-1946). I remember my gran, Margaret Jeffrey, telling me about him when I was a child and maybe that subconsciously confirmed something in me. I don’t think there was any kind of ‘road to Damascus’ experience though. I just started writing (very bad and very long) poems as a teenager and have never really stopped. Writing poems that is…pace the ‘very bad and very long’!

A Family Portrait

After she had died in childbirth,

Anne Nisbet’s husband, John Glassford,

first tobacco lord of Glasgow,

turned to the family portrait in his living room

and dug paint out of the weave that made her face.

Taking a piece of sourdough bread

he cleaned the vacant spot

then had the artist affix his third wife’s

head to Anne’s still serviceable torso.

She did not leave entirely

and tells me how she never left

the mansion’s orchard, stood

for centuries among the shades of apple

trees and leaves that whispered in the modern city’s

traffic, gazing in through absent windows

towards the place she knew the portrait had been hung.

But I could go, she said, stand before it and wave

back the dust, coax her features from shadows

that once had lips, a smile, a gaze directed at her husband.

And I could point too at the little black slave,

Josiah, whose face a later hand

had darkened further into drapery and a hollow

space whose emptiness echoed with a city’s shame.

Once he ran away: in a brown freeze coat

and a blue waistcoat, with little Scots

or English. He was described as ‘knockneed’

and just fifteen. Their lineaments linger

in the flakes, the scalings and blisterings

of time, remembered now and then

by ghosts like us before we fade

as well and the cities change again.

Which poets inspired you at the beginning & who today?

When I was at school I developed a crush on T.S.Eliot. Then I moved on to Auden for a while. My English teachers at Glasgow Uni really opened my ears to the wonderful poetry of the Renaissance and 17th century and I have an abiding love of Andrew Marvell, John Donne and Henry Vaughan. I keep going back to Marvell in particular, one of the most musical poets. In French, Ronsard was also important for me, as were Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Valéry and Francis Ponge. Rimbaud especially. If I had any moment of ‘revelation’ when I kind of saw a way forward for myself in terms of my own voice and identity as a poet it was in Paris in the late eighties when I read Rimbaud alongside Whitman and the Portuguese poet, Eugenio de Andrade. Quite a lot of prose-poetry came out of that combination. Today, these same poets remain with me. Others have joined me along the way, too many to mention them all of course but among the older generations in no particular order: Hugh MacDiarmid, Iain Crichton Smith, Edwin Morgan, Thom Gunn, James Merrill, Derek Mahon, Douglas Dunn, Michel Deguy, Yves Bonnefoy, Josée Lapeyrère, Rilke, Lorca, Jorie Graham, Elizabeth Bishop, Les Murray, Barry MacSweeney, Zbigniew Herbert, F.R. Langley…I read a fair amount of non-fiction and get as much inspiration there as from poetry. Derek Jarman’s cinema was also a major influence.

What compels you to create a poem?

There’s no set pattern or set of circumstances. But a need to clarify something to myself initially: this needn’t take the form of an idea or even an emotion or combination of the two. Maybe it’s more a need to clarify, to give shape to particular sensations and intuitions that say something about what it’s like to be alive now, in the present moment. Then the attempt to communicate this experience to others in ways they may be able to relate to. Poetry can be a way of finding out about the world but it can also be a kind of conductor of being. I think it’s taken me a long time to -only partially- understand the latter dimension.

What does David Kinloch like to do when he’s not being poetic?

My tastes are fairly ordinary. I work a lot and much of that is not about poetry at all but about communicating stuff to others and helping to make organisations and events of one kind or another happen. Otherwise I listen to a lot of music, mainly but not exclusively, classical, although there I think there is probably some poetic stuff going on in the background. I also love to travel. I love big foreign cities although in recent years I’ve spent a lot of time walking in the east neuk of Fife. Family and friends are essential. Oh, and I like boxing or slamming big heavy leather balls onto the floor of the gym.

You are currently the professor of Poetry and Creative Writing at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. How are you finding the job & what enthusiasm for poetry do you find among the students of 2017?

The job is quite demanding. We have a lot of creative writing students and not very many colleagues to teach them. As I’ve got older I have come to really enjoy (most) of the teaching I do and regard it as probably the most important aspect of my life. I used to think it was the poetry. That’s still important to me but it’s trumped by the pleasure of being able to pass on my own enthusiasms and knowledge. I’ve grown to enjoy it more as I’ve become more experienced.I find the students mostly very open-minded and receptive. Many tell me quite frankly at the start they’ve ‘never understood poetry’ but then it turns out half way through the course that quite a lot of them do write poetry and that gives us a good place to work from.

PORTUGAL

We saw the pelicans nesting on the lamposts.

Little bits of bad luck

spilled from their pouch-mouths

and drifted among the traffic,

catching smoking drivers by surprise,

making them swear. The pelicans

swore too: great barks

like belches seeking a nose.

The pelicans looked comfortable

and lonely. Ignored by everyone

they were the cause of everything:

the way the cycle lanes interrupted

the bridge which opened up

the pea-broth, iron-clad canal;

the way the right way went crooked

for us to the station so we missed

our train back to the dull resort.

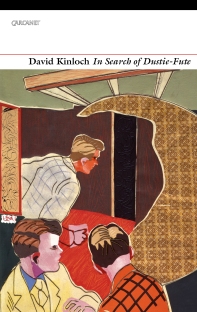

You have just released In Search of Dustie-Flute with Carcanet. How are you finding working with one of the country’s leading poetry presses?

I’ve published books with Carcanet since 2001 and am grateful for their advocacy. They’ve allowed me, mostly, to shape my own books and given me the freedom to experiment when I need to. That’s something I value enormously.

This is your fifth book with Carcanet. How has the evolutionary process as a poet been in this time?

Well, it’s actually my fourth with Carcanet. My first book was published by Polygon in 1994. Evolutionary process? That’s a very hard question to answer briefly though it echoes a question Stuart Kelly put to me at the book’s recent launch at the Edinburgh Book Festival. He suggested I started off as rather a baroque, expansive poet and had become more ‘honed’. I think he meant maybe I’ve just stopped writing such long, bad poems! It’s about listening with your inner ear, about finding a specific pitch or tone in terms of form and music. In terms of subject matter, I tend to write less about sex and more about art these days. Which is -sadly/thankfully- maybe just part of the ageing process. Actually, having just said that I think am going to have to try and reverse that particular evolution!

SINBAD

We crouched among the men with guns; silence

paused. Then, we smelt the air lightening

—a bouquet of ozone up from the port—flinched

at the sudden crash of sealed-up doors.

And stood again to crane and jostle

as the figures paced through the forum.

First, a slave girl, black as a shining moon.

Two statuettes of boy kings holding hands.

A gladiator spearing a vanished enemy.

A satyr. A Zeus. A discus thrower.

A sphinx as crippled and slow as us.

A stone maiden carrying a jar

full of the incense of spring meadows.

At night, we followed their procession

to the harbour and an ancient ship

where mist or a kind of gauze

wrapped and stowed them carefully.

The sea yawned like a snake.

The captain we could not see

cried like a bird and cast off.

In the morning all was gone.

And we knealt again.

What are the stand-out continuous themes running through your work?

Loss. All of my books are about loss of one kind or another. Although I try to wear the elegiac cast with humour. After that it would be sexual orientation, gender and ekphrasis (or writing about art).

What is the poetical future of David Kinloch?

To my surprise I’ve started to write a play so maybe I am about to evolve into another creature altogether.

December 19, 2022 at 12:36 am

Greeat read thankyou