Poets

Lyra: Bristol Poetry Festival

Lyra: Lyra at Heart

Getting into this year’s two week online Bristol Poetry festival was a joy in itself, with another fine example of online organising. This time the team of Co-Directors and social programmers had something striking to say and the festival‘s aim and title of Festival Reconnection. To say that something was afoot would be a good reference as to the way that online poetry can hold the audience who are just out of being knocked by lockdown though it has now been lifted and hopefully businesses are coming back. So let’s come back from this 2021 Lyra’s protective theme of total and real Reconnecting.

It fell to Prof. Nick Groom to introduce us to and capture us by his expert story of a Bristol poet named Chatterton or Thomas Chatterton. Prof Groom who is a speaker, published with his themes of range and identity, his books include ‘The vampire, a new history’ which I haven’t read and know nothing about. In the fact that Groom’s experimentation in lecturing itself, would bring his world of writing set to explore Chatterton’s influence on Wordsworth’s writing and more.

—

Lyra: Prof. Groom: Chatterton’s books

He looked at Chatterton’s work and took the single lines from his poetry to examine how the premierist soon to be a gifted writer and how he early on went into creating through his stronghold phenominality we could have called him a phenominalist. Chatterton’s stories were very much influenced by his take on equality but his immortally kind and understanding stature only lasted until his suicide at the very tender age of 17. His tragedy was sealed. This tragedy shows him probably to be the youngest poet ever to write with such clarity in these manners, matters and more.

A Chatterton Quote would be, “Flowereth nodded on his head”, to me meaning something very gentle, to his, “…to hear his joyous song.” a line to speak for itself. Through most of his light and striving the dedicatory lecture compared Chatterton’s world to the world of today; finding reconnection in his remarkable relevance in the world of today and at the hand of humane starting to rebuild.

The Lyra festival was presented in association with the magnanimously rich in literature; Bristol Poetry Institute. Of whom a Bristol poet Caleb Parkin was in conversation with Madhu Krishnan. Their task was to hold a definitive discussion where the reconnection of our natures will and other natures to be taken in; to drink in the vast possibility’s in future by way of for everything. Going into a better and further look into the world of earth’s nature’s and the powerful nature of Poetry, which is why we’re all here.

A special thanks has to go to Danny Pandolfi a Co-Director of 2021 Lyra and Beth Calverley this years honoured festival poet, who does no end of positive work using poetry to help people to express themselves, she goes deep into this work but from what I saw always with a smile and amazing willingness.

Listening to her charm the place she read her poetry like it was from the sky above. And I would like to thank the other co-director Lucy English who is a spoken word educator and reader at Bath Spa University and is a Co-Director of ‘Liberated words’, so there was a coming together of big worlds in the poetry scene. And I would like to mention Josie Alford who was Marketing & Social media management and is said to have quite a stage presence.

—

—

Lyra: In the Event Of…

This event saw a great discussion and Q&A with Danny and Lucy in the launch of the theme of ‘Reconnection’, and all of its physical, natural and environmental implications. That led to poet Caleb Parkin whose pamphlet “wasted rainbow” was commented on by Nadu Chrisman to open up a discussion about the institutes and live world of spoken poetry. With our interests at hand the feedback opened to being interactive and somewhat centred around lockdown.

With the ecosystem and ecology of poets resulting in greatly helpful organisations whose textured aesthetics, novel form, narrative prose, seemed to surmount looking like (and helping us look into)) the life of the tree who are like their own point of origin and conclusion, seeking the elixir. Brought about loud and important ways to try and treat language specifically in a different way (a term of service that can disintegrate words, and lays out language).

Delving and enveloping the interesting tension in a poem of the individual feelings and focus for the reader and the listener. All of which proving a fascinated interest in dominance and seeing life on earth as a tilted experience. As a kind of “…perpetual loading icon.” That obviously never ends, or a “…pixelated fish”, perhaps indicating no resistance. The philosophy and reaches of the proposed ethics of poetry, within the festival frame plan took us from tip to toe. Offering completed poems and breaking down these poems to see fundamentals where questioning is really quite stylish and purposeful in the field of where to get ideas.

—

Lyra: Frogs and ‘Liberated Words’

Fiona Hamilton’s “Smell of fog”, reached in and plucked a frog from a naked patch of earth. Whose metaphor struck the almost dumbed senses of frogs that can’t self-isolate! The frogs as a species are a perfect depiction for fertility and interrelatedness. And in this offering was held the deeply fascinating work of eco poetry in action.

As a further introduction to ‘Liberated Words’,who from humble beginnings in the 2012 which was like a year at the Bath Spa University. Lucy directed Reconnections in her screening of poetry films that for Lyra were heritage, family heritage and connection. Sarah Tremlet produced books of poetry films commemorating her much loved film genre. She is a poetry film maker, theorist, and author of the ‘Poetics of Poetry’ film starting in 2005. In her meeting with Lucy English in 2010 they connected and decided to make poetry films about teenagers with autism, all in the name and deliberation of Liberated Words. ‘Liberated words’ and the ‘Arnolfini’ (the Bristol international Centre for Contemporary Art) have hung out many times over the years to the benefit of both.

—

All of this in the Reconnections: Poetry Film Screening

And in the subject of identity of things like minors, where there may be a duo of poetics of place with 5 examples of Lia Vile Madre who was a medieval gypsy whose heritage collections led to the object of the film ‘A bird on a tree’. So came: the ‘Bird’ Poem’ which was a commission from the Centre for Arts and Wellbeing, literally at the top of the tree. As the poetic wheels of motion rolled along the lines went from, “…feathers always fascinating us…” grouped with, “…love’s me to the winds.” And “each new bird roosts for me!” all hailing a triumphant noise to the sounds and senses of an earthly paradise. Leaving us with feelings of “…favourite colours, rainbows.”

The films scanned one after another in their very short form. Taking us through extraordinary stories of what they called “scattered feather dust.” And spoke of the “bloodlines” of poetry filmmaking with new departures from Ezabel Turner whose pamphlet ‘Wonder of the traveller’ put bones on the road in connection with rural communities. So the film ‘Blood lines’ was in colour and of a green forest at hand. With “…open bravado door”, something sensual and similar, coupled with “songs and seasons wave at you”. All of which completing her surmount of the old depth of reading and writing.

—

Lyra: Identity in the Mirror

In further film mode of poetry it was seen by Yvonne Redicks whose words became something confident! That creating this world of lyrical semblances in the green and purple lines of, “that night is steep.” With “…ring of his ashes…”, and in the “…line of figures…” completing the theme with a terrific comment on “…still born brother.”

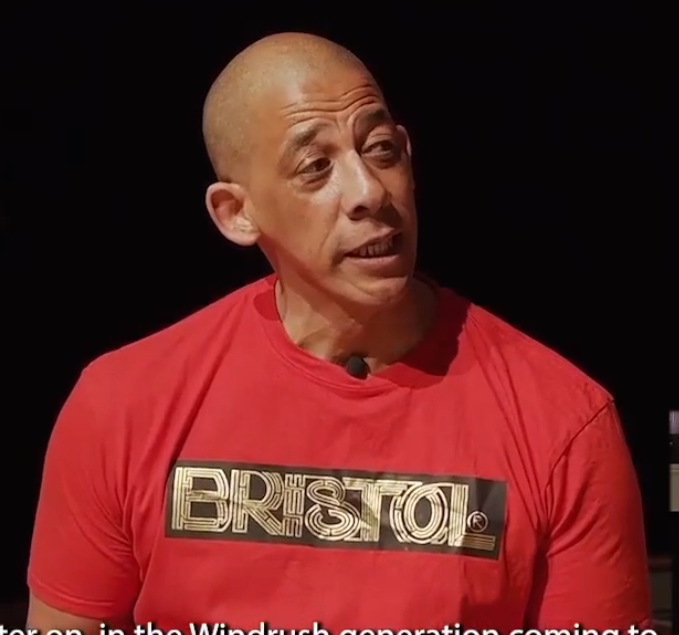

Moving away from film poetry we were invited right into a panel discussion that curtailed on programmes that were done and dusted, and showed us the many implications for thriving as a poet in the world of institutional and established themes whose opportunities being hopefully set to be fed and grow. Our discussion starred the inevitable voice of reason, Dr Edson Burton and with the voice of experience, Lawrence Hoo and facilitator (with some style), Ngaio Anyia.

The three of them were entrepreneurs at panel discussions, though there was a feeling of real relish from one being to another in this online way. Covering an abundance of tracks they talked about; Art & dissent: Bristol’s radical history. In this title the scope was placed for coverage to be their subjects and advertise them in the hope of bringing them to social matter.

About the plight of humanities African persuasion, communities build on being burnt to the ground classically, culturally and in the institutions. All of this has happened in what I can see as a sustained attempt to control these sections of the community’s across the world with a flag placed in Bristol at the Lyra. A jumping off point for Lyra was to heal the gaps of heinous injustices. I merely use this language because of how well the story was put together by the three even though only as a list of white crimes none of which were made with palatable events.

—

Lyra: Lawrence’s Analysis

Analysing Lawrence’s contributions against enslavement he looked at freedoms and civilisations, to build an unrelenting onset with his strength and willingness of experience. When talking with Dr Edson, the points were almost all reiterated. This was celebratory from the point of view of feeling free to speak out. The three did just that and asked us to do that too. There are so many things now going on in Britain, as to think something big may be happening, some kind of all-encompassing wave of truth brought about by writers and poets. But for the moment we will use the distinctive goings on in Bristol and in Lyra 2021.

Onto something inevitable in a made and unmade process. Keith Pipers words were eloquently articulate in a continuation of slave trade books, scenes and most importantly movements. And by now we were seeing familiar faces of the festival with for example Dr Edson talking about Pipers works and feelings. Also getting together with Meshin Decello and Vanessa Kisuule the animation films brought a presence that is unique to this type of art. Developing different voices and activism there was a direct energy alluding to a society that ignores poetry as it ignores people. But for that very reason the need is in offering a call of and for poets to be recognised.

In an examination of spoken word in the UK, seeing its history and significance, we welcomed Peter Bearder who further dissented the festivals accessibility. Looking at barriers he performed to the wider world with representative dealings and collaborations for presenting. Part of his creative, playful, physically competitive environment, and in the use of venues such as pubs and clubs. He showed us who could have the discipline for the performances and techniques. A surmounting elaboration of the modern music; dub, punk or hip hop. We could see the implications almost every time.

Though we frequently delved into the many themes of Reconnection the work was also brought into modern day focus. The focus that is needed to see our world as they expand in the relevance of the past or the past relevant to now as alluded to in Prof Groom’s sage like lecture in the events of Chatterton’s 100ds of years old legacy.

—

Lyra: Cutting Edge

Showing how surprising it is to see cutting edge life of many eras ago and in the time lines of seeing the future. Looking into the African situation of suffering can still be constructed by departmentalising it. Not the work or the poet but the theme. Pete used minority identities to compose and measure these abducted transferences. Cutting in with edgy progressiveness and offering a resistance against the all-powerful commercial marketing. Who if we look at it are also ran on a basis in slavery.

Using performance poetry to convey anything is always a striking phenomenon because of its nature, history and popularity. So for Langston Hughes it was a perfect opportunity to honestly talk about and discuss black America, and its history and its place in the world today. How do you cut through built up distrust? How do you even respond to terrible events? Again by breaking down of systems; for example exposure of Artists, or in the maturation of art form instead of the watered down work of the market.

—

—

Lyra: A Kick from Poetry Kitchen

In the aptly named Poetry Kitchen the in-depth knowledge took another turn at the deep end. Including and inviting us to the art of gathering scenes together by using criticism to provide a space for the hippest questions about the 20th Century. Spoken word phenomenon is as to what it is for having already been very impressed by it. It is a world where cherishing differences and critical language come together to agree on spoken word direction having already taken its place. Once again creating Reconnection’s and having a real love coming through bringing the delight of poetry into being; speak and ye shall hear. Lem Susey induced in us to a need for growing black poets becoming a very busy international hub to help create these things for communities and neighbours to share. It, as so much of Lyra festival is, grass root identity, to be striven for and used to debunk fresh acts of violence or the perpetration of…, to create a new culture with an open and tearful eye for the present as on the past.

—

Lyra: Reconnect

There was no end in this fortnight long online festival to the bountiful world of spoken or read or performed poetic‘s in stances and conundrums. All bound together and clasped together but all with poetic sincerity and connectivity in mind. Poetry of the world puts the highest thinking in place and watches with gentle turmoil as the acts of behaviour viewed across the globe. With this international conceptual thriving the reflections and commiserations shed light on the soul (or the planet) as a thing we know and will know for some time to come, even going back to the old religious celebrations. A healthy, natural absorption occurs; with the never ending qualities holding fun the day. Hence the festivals inclusivity of Lyra to talk loudly as with any other poetic organisations of today, in a world of bringing careful tenderness towards affliction’s of any kind.

This is how good and well the distributing of poetry can get out and to as many populaces and cultures as is possible, enter Beth Calverley who was festival poet 2021. She is a 2020 British Life awards and Arts finalist with a collection of ‘Brave Faces & other smiles’ to accompany her verse and poetry press releases. She makes the endearing step towards mental wellbeing for all with her workshops and projects. She performed with her good friend Bethany Roberts whose songs and spoken word had them smiling in different ways.

—

Lyra: Make the Reconnections, Final Word

The aptly named “Spellbound” was a work of genius. It held the reflection of so many things that poured out of the violin, the music and the voice. We could easily see why Beth is flying and why she was named Festival Poet; imagine the lives she has personally touched. Then to the poems and poets; what this comes down to is written word of poetry. The listening to it, imagining it, understanding it and always making it your own! I’ll leave you with some quoted lines to sooth you but also to wake you up;

The wonderfully positive snippets of a place where; “…the weather was awful.” to the reasoning response “…comfort eyes.” And “…sense my voice friend…” to “…hold this yellow thread…” leaving us with “…sing myself undressed…”

To the bleak “…ghosts don’t bring wine…” looking for “…gold wrapping paper.” But within a “…clammy abyss…”

It was the protest styles that grabbed us with plentiful ideologies of how things play out and come to happen I leave you with the line; “Some poems force you to write them.”

———————————————————–

Reviewer: Daniel Donnelly

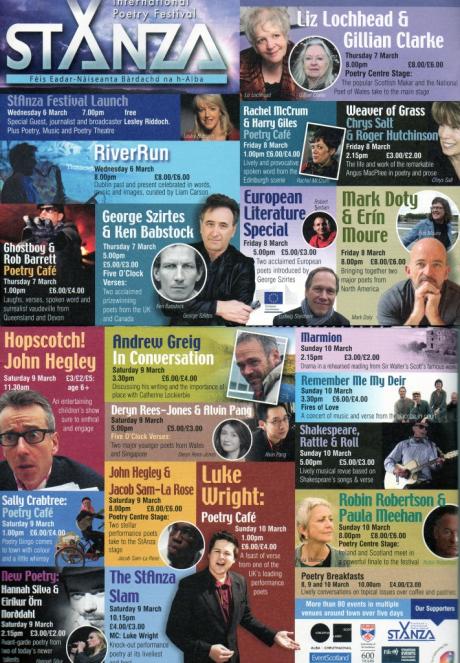

StAnza Poetry Festival 2021

St Andrews

March 6th – 14th

The Stanza International Poetry Festival took place online from 6th to 14th March. Stanza was born in 1997, the brainchild of three poets deeply qualified in the field, Brian Johnstone, Anne Crowe and Gavin Bowd. Over the decades it has built up a standing as a leading place at the head of world poetry. Brian Johnstone, the poet and writer, is part of Edinburgh Shore Poets, with a particular interest in live poetry. Brian served as Festival Director from 2000-2010. Anne Crowe has many publications and prizes, and has translated into Castilian, Catalan, German and more, and Gavin Bowd teaches in St Andrews University. The first Stanza Festival launched on National Poetry Day in 1998, only a year after its conception.

This year, there wasn’t a single poet who did not strive and succeed in the field wither older or younger. having many honorary or volunteered for positions in the festival life itself. But the top seats had to go to the amazing Eleanor Livingstone who took us around as the Festival Director, Louise Robertson, on Press & Media and Annie Rutherford, Programme Co-ordinator.

The pre-festival 5th March Panel discussion I found extremely interesting. I was captured by all the great styles of the written word. Taking off, with an expert discussion about the current goings on in the ‘European regions progress in literary culture’: an assessment of the progress culturally in considering brand new approaches. With an emphasis on understanding of the said European literary culture and regions, whether or not the writing is concerned enough with winning a battle of creating real roots outside the English dominant language. With the good news of their beginning to be or not of new infrastructures that are coming through with fresh lenses.

The Event ‘Trafica’, a radio initiative/European project talked very specifically about its identity and the giant world of creating serious funding that is met a little in the creating of inroads into how to qualify for funding. With Dostoevsky mentioned; the getting out of politics in poetry or at least in the intake of greater cultures, was dreamed of with the belief that poetry is of the Alchemy of the spirit and a gorgeous wish to move far away from being anything narrow minded. All coming with the initial supra courageous step of leaving your home country, finding its way to Stanza.

Concrete Poetry & Insta Poetry

My introduction to this came in a ‘Meet the artist’ event concerning the concept of concrete poetry and Insta poetry; The Insta was explored in Chris McCabe’s ‘For every day’ a poetry book with two poets in what is called a poem atlas, an idea of high mountains and frequent views both bad and good (to put it in simple terms). Bringing with it uncomfortableness and an openness which through the poetry went into the performances and readings.

Insta poetry is helping herald the quiet yet substantial revolution of poetry to the new and younger audiences. With its new forms of poetry, such as photo poetry. All made around the two fresh prospects of Concrete and Insta poetry. Giving the poets a chance to convey personal interests in the nature of concrete poetry measuring its effect upon itself with the natural components of words.

Political poetry then would have helped in the creating of a platform for forming options for the artist to reach their own outreaching platforms. They talked about the marvel that is online eventing calling it a dynamic in the world of Instagram critique. Astra Papachristodoulon asking us to travel beyond the book. Thinking instead about using her own brought objects to the table, a very wavy broadband of a subject. She also gave the example of using sculpture to make sense of her feelings, in particularly mixing sculpture with poetry. So, the highest abstracts were made possible in her very own art form.

The poet called Jinhao Xie spelled out more of how Instagram has brought a closeness to the audience and an interest in the poems themselves. But the aim was to use concise language and influence the critical gender performance, that leaves us with a chance of using simple graphics, with the all-important thing: humanity of others. His concrete poem where doors being closed, set to hatch his poem.

Found in Translation

From Found in translation (as to the popular lost in…) came a call to translators to show their form, their all-important co-working partner; interpretation. Tania Hershman, a poet and translator and Peter McKay communed online with Nicola Gevsky, who translates and interprets, and is into the fascinating, enthralling and necessity ways of the paving for us no less than as a world-wide phenomenon, which sounds like quite a thing, doesn’t it?

Nikola herself read from her poem written to be spoken of; an amazing people who nearly translate the world yet so humanly seek to make translating poetry into something directly close to fun. Saying that the instruments for writing do very well to entertain the senses of the human body all the way up to the mind as a meditation. We listened to the sound of rhymes as gold dust falling from the voices.

It seems that where there is an adopting of cultural context, there is room for expansion as in this case hailing from smaller countries. Translation takes place from the blood, sweat and tears of theirs and our revered poets who speak well in public. Though this is a thing that tends to differ per society (environment) and in their linguistics’ of the personal and the very public.

Backgrounds made the curtains of the theatre fall but it was always in pursuit of something fresh, lost and found is a good place to start. In the discussion on background of poems, there were translating challenges presented; to be handled by an enhancement in the learning about culture which is the passport to many things in the flight of this poetic world. It headed home to St Andrews with the translating from Gaelic of Peter’s piece, and Mitko Gogor’s into English. Putting the sharing of poetry at the forefront that merged for us into being very relaxed and finely in tune.

And in this relaxed manner George Colkitto (another wonderful name) who can understand full Welsh; again, portrayed another act of listening to the Welsh. He read these sounds like hymns of the human voice. Translating as a known and unknown quality where words and worlds still fall away. The ‘meet the artist’ events were always informative and super pleasant. And with the introduction of Peter MacKay who is among many other things a broad caster, lecturer, very much interested in translation of art and poetry into film. A question and answer, about the film poem just seen, was discussed with Ciara Ni E, a Berlin student with a deep and intense response to events.

Q & A on Found in Translation

Paul Maguire mentioned the occasion of choosing to speak in his own tongue, in the discussion and Pauls Scots, who speaks Gaelic Irish – wanted and does create the space for the handy opportunity to see the world through different lenses. And in the relationships between nations, whose translation into English has brought an external archive that was described as an ‘interesting process’ and with that the introduction of film, called a different animal ‘Urban fox’ an Irish sharing of cultures, stories, and a celebration of the ancient street scenes of Edinburgh ‘…fox eyes then her human eyes.’,

In translating from Welsh, words that didn’t fit into the interlocking of the process stood out, as the Welsh stands out as a language. Q. How much were you working from sound? Was a question that expounded the mediums and enhanced the subjectivity of the matter concerned.

Another Q. was. Is there too much emphasis of nationality in Ireland, Scotland and Wales? Which I felt was an electric question because it seems we would all like to know that one, a dynamic question for more wide spread thinking. Poetry has the ambition of representing entire cultures and in that world, they say that Irish and Scottish can very well be vice-versa in their substances. But there are feelings that Welsh is left to the side lines, mimicking perhaps a wider ignorance towards an anti-thesis that not all languages share the same usefulness as the mostly dominant Anglo English. In Wales there is a sense of a great lack of interest in the fineries of romantic culture as set aside by Rome

In the gaps in language, it is found that identity disappears. In for example closeness to masculinity undergoes misunderstandings, but in the spirit of determinism of subject there are important links succeeding between communities, snow balling since the big efforts for change affected in the 1970’s.

Online Organisation

Reaching remote communities is an exciting happening due to the internet’s reach, seeming to come to all of us here. It has among many other things created a different conversation online. The history side of things throw up great questions that probed into changes of attitude among nations. Where there is at the moment a longer process involved in Anglo Saxon world, because translation requires a wider questioning of translating older wisdom!

Maria Stepanova & Aileen Ballantyne, Two Poets

‘Poets at home’ where we met Maria Stepanova & Aileen Ballantyne event was of the downs of which the poet and translator Sasha Dugdsale incurred. In the voice of the downs, adapted by the nature of the countryside she is so very close to. For her it was everything, and her radiance grew with every piece of her dramatic and informational poems. Information that included methods for well mental being. But her soft voice spread out to the water or fields in front of her, almost with freedom at hand. ‘The downs – ‘wide open…’, a huge affinity…,’ laying her shadow into the picture as her ‘eternal feminine’.

‘The last model’ – Francise Boutle (2020) – Latgalien poetry to showcase appeared last year, who having formed broad international contributions in a minority language had Jade Will, a compiler and translator, own work ‘The last Model’ – 2018, Published (Boubly publications) – In the translated from Latvian into English the poem her ‘…age of Christ…,’ The last days of the Soviet Union, belches of Soviet era. The power of poetry, the power of Russian poetry, is a power and blood shed of war.

Taking in Topics

The power of translating from Russian into English results in desperate and yet very strong words, coming from a shift in history, that is to be taken very personally. So, reading two, three, four poems fresh from the press started coming from the same place in literature but differing greatly in environment.

The subject of describing woman and defining woman, often led to some horrible histories both personal and societal (societal should be easier to change for the better). Offering first-hand accounts, of the sheer pain of war and destruction that happened in the native or visited countries and regions who all share the same map. Woman have never been dismaying into backing down the extremely withered sensation in a battle of the sexes.

Nature takes its place in the heart of the Stanza’s proceedings, and by the looks of it a learned poet can be as clear as a country river with its objects and musings all in the power of poetry that bends like nature to your will wherever it may suit you.

Where in any line there was loveliness and hope at any other time the words and ideals disrupted our gentle walk and took hold of us to the very collar. Also, though not so much imagined sorrow but very real and now, holding poetry to their hearts or casting them very far afield. Always returning to the magic that poetry seems to have a place for all of us.

The Foreign Language & Finance

Estonian poetry had a good presence, with the positive news that some things are as good as on the right track. To the esteemed concrete idea of being a poet who earns a living. From the Latvian situation comes a revealing of wide spread publishing. And it looks as though it differs because of a problem of language acting as a stopper, that this process is proving hard to understand. But the line out of it would be in making the poetic market a non-government organization, and the organization of friends to establish publishing, leaving off for a need of more future progress.

Another New Poet

The Stanza 2021 Poetry Centre Stage events had varied poets who have been internationally sought after was Russell’s readings that had his close adherence to poetry through science fiction, to throw open the field and the day. His images with poetry crossed genres and moved into a new way of sending a message through poetry. His writings and compilations all worked in pushing things to an extreme.

Stanza: Masterclass

The ‘My Favourite Poets’ time was spent in producing a masterclass. Where from dark words, the hero poet knee deep in failure, bitterness and then joy, was like a scene from some unmentionable tragedy reported through praiseworthy poetic Stance. As a woman wrapped in insignificance. Reminding us of the wide and well spread coverage for exemplary poetry and factual utterings.

Helen Boden, Suzanna V Evens and Jaqueline Saphra

As we were joined by Helen Boden, we took a virtual walk along Fife coastal path. For which she amounted her poems and photographs from Yorkshire. With extensive collaborations, responsive poems and creative non-fiction under her poetic belt. She was so soft and full of great endearment, passion and accomplishment. Photography or film merges very well with poetry and creates a view of sight and sound. She celebrated her land marks of sheer familiarity for her that included the poems celebration of a light house that see the high winds and seas.

When Jaqueline Saphra joined Suzanna V Evens the experience heightened for me with the language she used in the forms of Form & evolution, in Suzanna’s terms it is something like or exactly like a palace of words. Or rather her term of the palace of poetry.

Her injection of this metaphoric place; the palace of poetry led us to understand her loud cry for this palace, as somewhere we could reach for or entre at will. She spoke of her wish to be inspired into claiming and taking over this palace which to me had a feeling of the epic poetry of old. To realise the struggle of the work of word. Leaving us with the epic quest of what it might be to create a formless poem?

Post the Palace of Poetry

Read aloud out from a Fatal interview of St Vincent Mallet who spoke; ‘in the winter stands the lonely tree…’ sparked a rich discussions with Eavan Doland’s whose point of view was both agreed with and disagreed with. About the art and against the silence. Of a combustion engine that belongs to everyone, she takes note of a Yeats poem called ‘leader of the swan’, which is a horrific poem about the indifference of men to the scene of rape! I feel sorry to mention that here but maybe my feelings should waver here. She took us through how poetry has been shaped in our earliest stanza of the more pure and innocent prayer and lullaby, which was remarkably built to be remembered(imagine that).

So, onto Stevie Smith whose black and white film was directed by his stringent found truths that are in sense and music, and how again they can be used as a back-up for poems, his subversive style revolutionised the sonnet (no small thing). And for Eavan Boland, Marlyn Nielson, Gwyndelin Brooks the embracing the sonnet is most powerful potential for poetry of its two-line sentencing and short hand but lyrical object.

Spurring back to Eavan Dolands in the sense of the staying of woman in the broad sense as love objects. With a longing for breaking down from her fiery motif of moving the wall of the palace, as if holding a sword to the air. And with a sad push comes the recognition that poetry ignores people, or at least that may be how it appears at large. Which was a frequent comment fit for discussion and holding to the poetic torch.

Entering a zoom discussion was always bubbly and filled with the joys, Though no less discursive. We talked about the limits created by the currant and older problems of isolation of the senses. Coupled with the opposite track of internet wide coverage for the poetic world to emerge into. There is a lot to be recognisable in for example the music and metre where ability to conduct poetry is to try everything right up and down the harbours of the mind.

A Suggested Unison & Inclusivity

In all the work of the poet’s poems there seemed to run an undercurrent of a spoken unison. And at this year’s online festival, it was very successful that is to say very absolute in the faces of many frustrations that are holding unhelpfully back the literature movements. Some of its drive was of poetry that is not being held with quite the esteem and potential as it could be in the arts that convey it.

The inclusivity of the festival was paramount to the weeklong presentation. And when in the inspire sessions, we were given some gifts of direct techniques and of tackling the prospect of making works yourself. Showing something for everyone from well-established poets who so magnanimously shared. Making the poetry mostly into a taking off leading us far in and out of ourselves just by the act of listening!

No poem had less than 2 lines of topic of subject; creating a wonderful addiction to the gentle reassurances that were often to exorcize a turn of listening to a person talking in a language I’m sorry to say I didn’t know. In the Q & A and in the discussions, post reading offered the time for these considered people to reveal their trade.

Centre Stage

On a Poetry Centre Stage event Mona Kareem, a featured writer met with Michael Grieve a Fife poet and teacher and who has been involved in Stanza before, offered a little correspondence through some poetry. In an endearing poem by Michael, his lines were about time and thinking and contemplating to look beyond his own words and performed as a living dedication to some sweet ideas for living in the planet.

The bitter hero set to last only for a small time, or to be disregarded anyway had the writing seeking for a purity of living that won’t be found in anything less than an honest one. Weaving around the straight English poetry was the translating effect from English to Another or another to English. The Gaelic language held a fore front as well as Russian.

The writing covered seemingly every aspect of life. Using far-fetched facts about frilly concepts that were splayed by the continuous almost threat of darker things to come or those that have already happened. To put Kareem back into the centre stage event found that his ever-growing process had fired off with the increased use of as many forms of poetry as he found was possible, putting his work right out there to be studied for years to come.

The poets, the staff, the volunteers shared a feeling of great togetherness when going through all kinds of poetic certainties and more importantly uncertainty.

Kareem’s poetry makes things easier, subscribing for that, poetry can save the world, hit us with her ‘Femme ghost’ project. Through which she in no uncertain terms reclaimed her right to be more than the degradation that man always makes of her. Writing lines that really do change the world by bringing them into focus.

Beginning the Conclusion

Not a point was missed in each event that was so discursive to an onlooker like me. So many things were mentioned and so many discussions witnessed the glee of what it takes to be colleagues in the field. With striking questions and well covered subjects.

Winsome Monica Minott, a poet and chartered artist, was a Jamaican born young and emerging poet. An award winning, freshly published seeker for human rights for her country of origin. Had with Zion Roses created an historical journey in the voice of the Caribbean. There was more seriousness and passion in them as to make it from the heart of their culture and sad history of perpetrated violence upon centuries.

Giving many stories of how these artists became interested in poetry in the first place and a lot of them found that it gave them an inner voice. Something that grew and grew in personal strength and also in the world of awards, publications and collaboration inherent in that world, using a fundamental tradition.

A Big Thank You

Poetry can lend its hand in navigating history into its specifics. And during which time it creates hybrid languages, in the shaping of it. It has over the years encountered singular great and sudden changes led by individual people concerned with the history of the voice. But the signs go up again reminding us of the potential for hampered growth, disconnection, and of things that seem like they should not be. There needs to be a departure from standard English into fresh language as the poetic voice itself would instruct us to go.

Kate Tough, Lisa Kelly, and Greg Thomas were grouped together in an interesting discussion about the fast subject of ‘Making it new’, where there was a sense of optimism. And there was more of challenging the norm, looking into an extended field of choice that can grab the world from the few to the many. As is with creative writing metaphors came thick and fast. Having experiments to confirm or deny any given thought or feeling. With the concrete poetry either distantly or confrontingly standing as an outstanding new field.

Daniel Donnelly

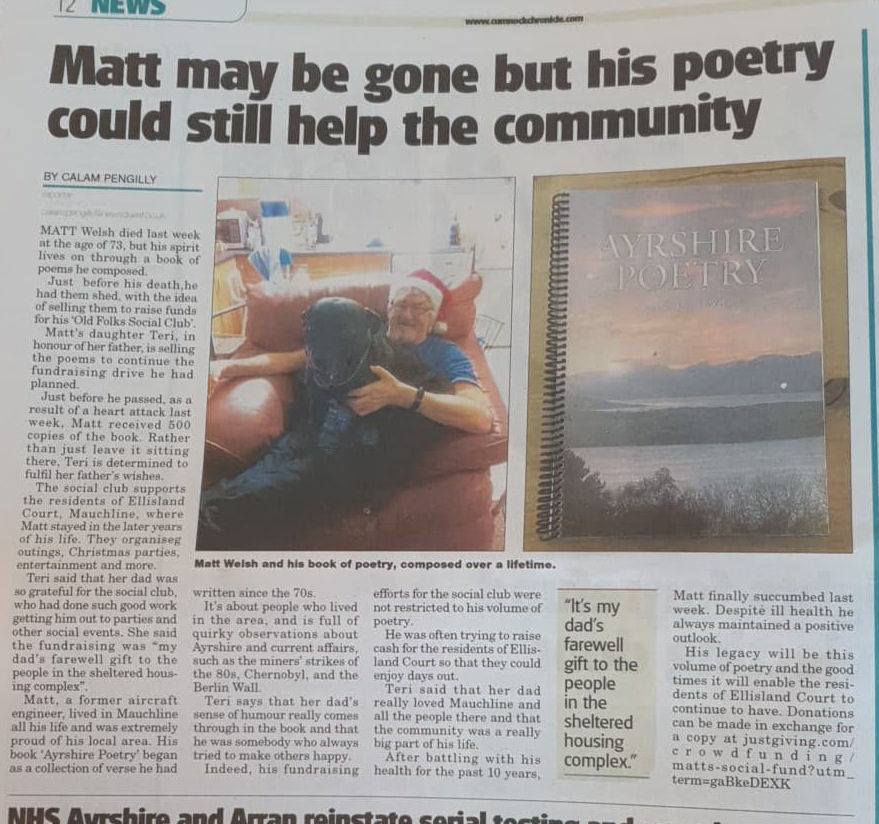

Matthew H Welsh: Ayrshire Poetry

Matthew Welsh passed away last October, to the great sadness of both his family & an intimate circle of friends, many of whom had been lifelong companions during his domicile in the Ayrshire village of Mauchline. This wee pretty place, & not incidentally, saw the birth & earliest years of Scotland’s national bard – Rabbie Burns. Now Matthew’s death might have passed us by like countless millions of others in this world, except for one thing, & that is a collection of a couple of hundred poems he’d been working on in the twilight of his life. He had intended to sell this poetry collection locally, to raise money for a local charity. Sadly, he passed away, but his family have distributed his book across Scotland, fanning his first flames of a posthumous fame that are kindling fires of appreciation in those who love both poetry & Scotland.

Live Long & Prosper

A hiv mind when we wis younger men,

We went pub-crawlin’ now an’ then.

Aff tae the dancin’, we wid go,

We wis quite hansome, I’ll huv ye know.

We wis always winchin, a bonny lass,

Dancin’ roon the hall, wi’ a wee bit class.

We’d arrange a date, fur Saturday comin’,

But wance again, we wid get, the blin!

Noo we’re aulder, retired folk,

In a basin, oor feet, we off’in soak,

Then tae a pub, fur a seat an’ a heat,

An’ a blether wi’ mates, we sometimes meet.

O’ times gon past oor memories tell,

Man, auld age disnae come itsel’.

Good lifes tae you, long may you live,

As good a life, as your life can give.

An’ so this poem comes tae an end,

Tae Mauchline folk, awe the best, I send.

An drink wi’ me, tae times gon past,

Us Mauchline folk are here tae last.

So welcome to the Ayrshire poems of Matthew H Welsh, a friendly romp thro’ a man’s life & times, a literary biopic bristling with beauty & intelligence & a massive breath of fresh air in a world of unpoetical poets. Like his illustrious countryman three centuries before him, Matthew chiefly wrote in the galloping & charming dialect of Lowland Scots. The poems he present us are all dated, beginning in June 2012 & the last dated September, 2018. Not all the poems were composed on those days, a good many poems are revisions of older pieces; in total a nice mixture of old & new revised by a mind focuss’d on its literary legacy. Y’see, Matthew was ill, & his poetry reveals as much, & in fact the key beauty of his work is the steady revelation of a dying body – tho’ retaining at all times an eversharp minded. It reminded me briefly of the AIDS poetry I have studied in the past, but these were generally composed in a state of pregrief & pathos, but Matthew takes his ailments on the chin, spinning them with a cheerful resolution to enjoy even the tiniest things in life, like his love for coffees, which get about 3 poems in the collection. The following stanzas are taken from various poems, which show his illness taking hold. To read them invoked Anne Frank & her diary, with her thoughts of Gestapo HQ transmuted into Cumnock Hospital.

Up an doon the stair,

Add tae this the pain am in,

Ma stomach’s awfy sair.

A’ve got tae shift at a meenits notice,

As fast as I can go,

In case a huv an accident,

Coming fae doon below!

Auch Well

A must be getting’ a wee bit senile,

A forget whit am da’in, every once in a while.

I go upstairs, then a come back doon,

Ma heed is burlin’, roon an’ roon.

Aye Dementia is, an awfy thing,

A forget the words, o’ songs that a sing.

Yet a’ve mind o’ things a did, when a wis a we’an,

But yesterdays a no-no, a think am goin’ insane.

Ol’ Age

A’ve finally done it, a’ve filled in the form,

A’ll send it away when I rise the morn.

Fur a wee’er hoose, wi’ nae upstair,

A canny climb them ony mair.

The W.C. is at the tap o’ the steps,

I trip an’ fa’, hurt ma knees an’ hips..

Am fed up takin’ ma life in ma hon,

Tae a flat or a wee’er hoose am gon.

I’ll Have Tae Pack

The physio’s have goat me, excersizing ma leg,

Tae build up ma muscles ’cause they’re flabby an’ sag.

I’ve missed awe ma pals an’ the barmaids but a ken,

Determined I’ll walk, tae the pubs once again.

Happy Days

I think I am shrinkin’, am awe limp an’ bent,

Ma get up an’ go, has got up an’ went!

I’m findin’ it hard, tae walk a few yairds,

Ma young days returnin’, isnae oan, the cairds.

Its difficult even, tae cut up ma dinner,

I’ll hufty eat soup, tae stop getting’ thinner.

A canny even chew, weel cooked roast beef,

It’s a long time since, a hud ma ain teef!

I’ve Seen Healthier Looking Shadows

So, in 2014 Welsh moves to Ellisland Court in his immortal Mauchline for a Keatsean domicile, overlooking from his bungalow window his own version of the Spanish Steps. I’m sure he woudl have enjoy’d the fact the Ellisland Farm near Dumfries was teh cooking pot for many of Rabbie Burn’s finest verses, including Tam O Shanter. The poetry slows now as his illness debilitates deeper, but he’s still happy & healthy enough to enjoy his 70th birthday as presented in the collection’s penultimate poem.

Ma 70th

Thank you tae ma two lassies, Trudy and Ter, who put on quite a show,

When a celebrated my three score years and ten, thats 70 yes I know.

They held it in the bowlin’ green, where the staff wis awfy guid,

Wee Stevie played guitar, moothie, banjo an’ saxaphone, among ither things, so he did.

Wee Arlene, a northern Irish Lass, she made chuck fur every wan,

We ate away tae oor hearts content, whie Stevie sung anither song.

Half wi through a wee surprise, Jim Cartner played the pipes,

Wi’ stampin’ feet an a yooch or two, the place wis fu o’ hype!

Tommy Mulgrew, wis on the ball, singing fur awe his worth,

A great wee nicht hud wan an awe, a great way tae celebrate ma birth.

Trudy and Teri gave us a song tae gie Stevie a well earned break,

They soonded awfy guid tae me or mibbes the alcahol in ma drink.

Last but not least ma guests who came, maist o’ them invited they surely filled the club,

A hope they awe enjoyed themselves an’ hud a celidh, It wis like a great big pub!

I thank you all, ma family and freens fur awe the cairds an’ such,

An’ fur awe the lovely presents and gifts, I thank you ver much.

A near forgot ma birthday cake, it really wis a stoater,

Wi’ ma poems written awe ower it, anither present fae ma daughter,

A hope ma visitors awe goat a piece o’ ma cake tae try,

Cause fur masel, again a got fur diabetes, two pork pies

A great nicht!

Matt 21/08/2017

Of Welsh’s other species of poem there are two main types. His set-piece odes reflecting the main national & international events of his times are the weakest, I’m afraid. But no poet is perfect, & this set does help to place the early Welsh in his proper time frame. We hear of the Falklands, Chernobyl, the Miner’s Strike, the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the Poll Tax, the Gulf War, & the final theme, the Scottish Referendum of 2014 after which Welsh writes (from ‘Paradise’);

There’s a place on this earth, that’s a pleasure tae be,

Its a place where my chest, rises up like the sea.

Filled with pride my heart thumps and it courses with blood,

This lands built with well-being, a present from God.

From the highlands up north, to the lowlands down south,

From mountain tops, rivers flow, to the sea at its mouth.

We have Bens and their Glens and we’ve Lochs by the score,

In this place that’s called Scotland we couldn’t have more.

We have oil, we have gas, we have plenty to eat,

Seas teaming with fish oor haggis is a treat.

He’s given us everything, God couldn’t do more,

Except for our neighbours, the English, next door.

They’ve stolen oor gas and they’ve stolen oor oil,

They’ve moved up to Scotland and stolen oor soil…

…This land that’s called Scotland, that’s heaven on earth,

Will belong once again, tae folk Scottish at birth.

When ye go tae the polls in September this year,

An you cast your vote for independence its clear.

A ‘Yes’ is for freedom tae do as we please,

Nae pleadin’ Westminster on oor bended knees!

It is when he writes about his family, pets & friends that he transforms his muse into a raging queen of musical wordplay, quality phrases, & elegant rhythms & rhymes. He manages to turn Mauchline into a Broonsean pantheon of pubs, pals, gals & laughter. The opening poem of the collection, Mauchline Holy Fair 2012, is a classic example, transporting us into a Tam O Shanter display of fairyfed revelry.

Mauchline Holy Fair

I went tae Mauchline holy fair, wi’ oor Teri, David an’ Donna,

The screamin’ preachers they wis there, fu’ o’ their ain persona.

We donnered roon aboot the stalls, o’ which there wis a wheen,

There wis plenty fur the we’ans tae see, the likes they’ve never seen.

There wis pipe bands here and brass bands there, the music wisnae rationed,

Awe the folk enjoyed themsel’s, as if goin’ oot o’ fashion.

In the kirk a choir wis singin’, like angels way up a height,

If Rabbie wis there tae hear the sound, mair poems he wid write.

In the bleachin’ green, big ba’s wis rollin’, wi’ wee boys bouncin’ inside,

There wis pigs on spits, hot dogs an’ burgers, an’ plenty mair besides,

Plenty tae eat and loads tae drink, an’ the sun began tae shine,

Yes everywan enjoyed themselves, that day had turned oot fine.

Kirk James he sang some Scottish songs, he set your feet a tappin’,

Wi’ the Glee club music, jugglers an’ clowns, everyone wis laughin’.

Twas there we met oor Jean an’ Sam, queuin’ up fur chuck,

We met again in Poosie nansies, got seats, we were in luck.

Then ma faither an’ oor Jim came in, an’ big Rab started playin’,

The pub wis really busy then, when wee Stan started singin’.

Yes everyone enjoyed themselves, at Mauchline’s holy fair,

A canny wait till next year comes, tae enjoy it awe wance mair.

Just when a thought awe the fun wis bye, as a donnered up the scheme,

Then a landed in an auld pals hoose, fur a few drams it would seem.

Oor Thorie,Morag an big Tam wis there, along wi’ Marlene an Griff,

Morag never laughed as much that day, though she wis a wee bit rough.

We had some laughs, we had some fun, that day we will remember,

The second o’ June, 2012, at Mauchline’s Holy Fair.

When thousands o’ visitors came tae oor Toon, just tae pass some time,

They’ll be welcome back again next year, fur the sake o’ auld lang syne

For Matthew, the Mauchline muse, that world of ‘weans & women & men,’ involves either him nipping to the pub for a drink, an epistle to a friend or the convocation of a happy childhood thro’ misty & appreciative eyes. The following stanza gives a brief taste of the flavour of this lyrical stew.

There were forty-four we’ans, awe in wan class,

Every wan o’ us noo, has a Scottish bus pass,

Big Harry an Mo’, Tommy an’ Gal,

Just some o’ the boys, an’ we are still pals.

The lasses were lovely an’ still are I know,

Helen, Heather, Christina an Maggie are braw.

Its amazin tae think, after all of the years,

We still stay in Mauchline, maist o’ us dears.

(from Classmates)

Matthew adds something different to his canvas, concluding his poems with a brief ‘Authors Note’ which sheds a little extra gloss, revealing his emotional tenderness & snappy sense of humour. Such a spirit is there at all times in his poetry, & tho’ his body may be resting the eternal sleep, that spirit he poured into his verses shall remain forever. And verses they are, true verses, steep’d in a native tradition, for Welsh is a poet unadulterated by the fashions of modernist verse libre & slams, & for that reason his poetry shall remain an island of long-loved lyricism off the coast of Ayrshire, while so many other oeuvres are wash’d away by time’s flood, realising the ambition of Welsh’s shortest pieces, ‘A Poem.’

I wish I could write a poem, that people would read and read well,

I wish I could write a poem, that people could tell and retell.

Someday I will write a poem, recited again and again,

Someday I will write a poem, recited by women and men.

An Advertisment for THE MALTIAD

I had gotten the feeling it was a now or never moment. On the eve of a new national lockdown in the United Kingdom I caught the last scheduled flight between Edinburgh & Malta. At twenty past six in the morning! This meant getting up at 3 AM & making my way from Leith Links to Edinburgh Airport, all the time following the results of the intriguing Presidential election in America. By the time the plane took off I was already becoming resigned to four more years in Flumpland.

Four more years! Four more years!

All optimism disappears

I’d rather vote for Britney Spears

Its four more years in Flumpland!

An hour’s sunrise later I found myself looking out of the small window at the south-snaking rivers of the continent, over which hung ribbons of mist & dew. Two hours more passed atop the white rolls heaven, before breaking out into open skies a few minutes shy of Sicily. What a perfectly timed moment it was as I spotted below me the three islands of Favignana, Levanzo & Marettimo – formally known as L’Isola D’Aegadi. It was in 2007, on an extended visit to the furthest out to sea of the three, Maretimmo, that the Maltiad drew its first breaths. The background was a Mediterranean wintering in the style of the Romantic poets, accompanied by my lovepartner at the time, a farmer’s daughter from Dumfries called Glenda. I had persuaded her to give up her house in Edinburgh, which we had shared for two years, & have an adventure far away from the cold of a Caledonian winter.

READ THE MALTIAD: SONNETS & SIEGES

After spending two & a half months in Sicily, mainly on Marettimo, we then decided to explore Malta til the spring. We arrived in this glorious jewel of an archipelago one late January morning from the port of Marzemi. There then followed two months of residence between Malta & her sister island, Gozo, the poetical product of which are Calypso’s Cave, the Maltese Falcons the last four of sieges to be found in the Maltiad. The other siege, that of Gozo in 1551, has just been composed on my second winter’s visit to the island, in late 2020, as were the vast majority of the sonnets.

In 2007 I had kept a group-email type Blog, in which my Maltese experiences were poured into & stored for posterity. I give the following as an example;

GONZO GOZO

The Maltese sure know how to party & I have now got one hell of a hangover. Lent starts in a couple of days, & the Maltese have been raving since last Friday – AND ARE STILL GOING! They have a mad carnival on Gozo – carne vale means without meat – & for the next forty days that’s what they are supposed to do. There is a town on Gozo called Nadur & basically half the Maltese population turn up (200,000), rent the pads that are normally filled up in summer & unleash their libidos in all directions. There’s a constant procession of dj-floats & costumes from about 8pm to 6am – EACH NIGHT! Got dressed up as a blood-soaked serial killer on Saturday, but unfortunately I got drunk & subsequently lost he group – no wonder I didn’t get too many responses when I asked for directions. I did manage to find Glenda & our party in the end – a mixture of Maltese, Serbians & Glenda’s mate, Festa – & have just woken up from a two-day sleep. I’m trying to get my head back together again as I had set off writing the Maltiad – a number of poems for Malta which I’m trying to squeeze in before leaving.

I am beginning to tire of the sonnet form a little now. A year of intense composition in one form has seen me grow deep roots into rosy-bedded sonnet-lore, but at the same time, as familiarity breeds contempt, I feel ready to try new modes of poetic composition. One of my first new efforts is set in Calypso’s Cave, near where we are staying. In the Odyssey, the hero gets enchanted by a sea nymph called Calypso & forced to be his sex-slave for seven years. It seem’d a suitable place to share the seven-century-old customs of Valentine’s day, & we made a midnight picnic there, lighting the lovely pad with candles & knocking back the wine, perch’d high over the moonlit magic of Ramla Bay. As we snogged to the sounds of the sea, this was surely going to be my most romantic Valentine’s night ever.

Marsalforn

20/02/07

READ THE MALTIAD: SONNETS & SIEGES

Fast forward t0 2020, by the time I landed in Malta that early November morning, the urban votes were beginning to pour in across America for Joe Biden, rendering obsolete my hastily dashed off high altitude quatrain. What was not obsolete, however, was my affection for, & devotion to, the art of poetry. Back in Malta after fourteen years, I was a different poet to the thirty-year old who left here in April 2007. I would this time be utilising the National Libraries of Malta & Gozo – two fine institutions curated by three very friendly, noble & eager-to-help gentlemen. In Gozo, a Knights Hospitaler called Chris Galea, & in Valletta – Louis Cini & Donald Briffa. Asking the latter was he Scottish, he replied no, his mother was going to call him Adolf but was dissuaded by certain nuns, & a substitute name was quickly given! Both libraries were cereberally conducive to academic endeavour, & there was something wonderfully traditional about being in the Valetta version especially. This was the old library of the Grandmasters, which you could at one time access directly from the palace. Entering it for the first time is a moving experience – wall to wall with old books stretching into the cathedral heights of its ceiling, & of course wooden catalogue boxes & the dewey decimal, system accompained by reams of beaurocratic forms filled out in triplicate!

The product of my two working winters in the archepelago is The Maltiad: Sonnets & Sieges. It is, of course, divided into two sections. The sonnets are divided into geographical regions & constitute a walkable – or driveable – circuit for any future tourist to these islands who enjoys reading a poem where it was set. Their subjects are a combination of meandering happenstance, for as Wordsworth himself wrote – in the very year that Napoleon invaded Malta-; ‘it is the honourable characteristic of Poetry that its materials are to be found in every subject which canm interest the human mind.’

There is also a grand sequanza – that is to say a family of 14 sonnets – in which I have collated a number of the famous Maltese proverbs. The form I have chosen is definitely not maltese, being the kural form of the classical Tamil poets such as the Thirukural of Thiruvalluvar. However when dealing with aphroisms, I have found the form to fit so readily perfect again & again. In essence it is simply a couplet of four words on the first line & three on the second.

Sellers have single eyes

Buyers one hundred

Most of the sonnets, including the proverbs, may also be found in my Silver Rose odyssey, an epic poem’s worth of sonnets, 1400 strong. They fit into the schema betwen my trips to Sicily & Greece. Posessing pretensions of epos, I have also composed an Iliadic piece entitled Axis & Allies in which two of the Maltese sieges are incorporated – those of 1565 & 1941-42. The 20-line form utilised by these sequences I have personally designed & named the ‘tryptych,’ & is used in all 900 stanzas of Axis & Allies. Of the remaining poems, Calypso’s Cave is, admittedly, not much of siege – but recognizing poor Odysseus was kinda besieged, I allowed it into the mix – Sonnets & Sieges just sounds so good.

Since the last time I was in Malta & Gozo I had also become something of a historical detective, attempting solutions to famous mysteries such as the true identity of King Arthur. I’ve called the discipline CHISPOLOGY, after the principle of Chinese Whispers, or the ‘Arab Phone’ to the French. Never one to miss a chispological challenge, I have come up with at the very least plausible answers to two of the great Maltese antiquarian questions – what is the etymology of Malta & where is Calypso’s Cave. I have touched on the answers in two of my sonnets, but feel a little more depth may be supplied at this point

The name Malta is said to derive from the Latin Melite, whose origin scholars have placed in two camps – either from th Phoenician mlṭ, meaning “refuge,” or from Ancient Greek melítos, meaning “honey.” Let us instead acknowledge that according to Greek myth, Heracles mated with a nymph called Melite.

Melite bare to Heracles in the land of the Phaeacians. For he came to the abode of Nausithous and to Macris, the nurse of Dionysus, to cleanse himself from the deadly murder of his children; here he loved and overcame the water nymph Melite, the daughter of the river Aegaeus, and she bare mighty Hyllus.

Apollonius Rhodius

Hyperia was the island home of the Phaecean people before their resettlement on Scheria. One of the oldest historians to write about Malta, De Soldanis, states that Malta was ‘Iperia’ & the Phaeceans were the ‘Faeci.’ The key passage is;

Soon after the trouble with Ilium the Phoenicians took the island of Iperia or Malta after they had expelled from there the Faeci

The reason for their exodus from Hyperia under King Nauthilous was pressure from the neighbouring Cyclops. All this is given in the Odyssey, from the lips of the Phaeceans themselves.

Athena went to the land and city of the Phaeacians. These dwelt of old in spacious Hypereia hard by the Cyclopes, men overweening in pride who plundered them continually and were mightier than they. From thence Nausithous, the godlike, had removed them, and led and settled them in Scheria far from men that live by toil.

According to another very old writer, Thucydides, among the “earliest inhabitants” were the Cyclopes. Joining all the dots basically makes shape rather like Malta, & suggests this particulary Melite was named after the lovepartner of Heracles – remember their was once a huuuuuge temple to Heracles in the south of Malta, surrounded by a 3 mile wall.

My other chispological discovery is also connected to the Odyssey – that of Calypso’s Cave. Indeed, the close proximity of the Phaecean & Calypso elements in the text suggest some kind of common origin. The most enduring location of the island cave where Odysseus spent seven years as what amounts to a sex-slave to a goddess, is on Gozo, at Ramla Bay, but of course there has been many other contenders. In 1790, Richard Colt Hoare wrote;

The identity of the habitation, assigned by poets to the nymph Calypso, has occasioned much discussion & variety of opinion. Some place it at Malta, some at Gozo, & others elsewhere. At all events, we may now seek in vain, either at Malta or Gozo, for those verdant groves of alders, poplars, & the odoriferous cypress; for those meadows, clothed in the livery of eternal spring; for those limpid & murmuring streams, with which Homer adorns the abode of Calypso

My own contribution to the debate is that yes, theGozitans wer right to preserve a folk memory of Calypso on their island, but no, it wasn’t at Ramla where she kept Odysseus as a sex-xlavwe for seven years. Instead, the extremely ancient temple of Ggiantija at Xeghra is the original Calypso’s Cave, & a factochispp took place over time which moved it a couple of miles to the coastal cave at Ramla. However, there is no evidence of some kind of religious sex thingy going on there, but there is a lot of evidence for that kind of thing happening at Ggigantijia, such as fertility goddess statuettes & a temple shaped like ovaries. The egg-like rooms could even have been used in some kind of orgiastic ceremony – but that’s pure speculation on my part.

The longest piece in the collection concerns the Siege of Gozo, 1551, which also has a place in the Conchordia Folio. This is my collection of musical plays in which the dramatic elements are often given a Shakespearean linguistical twist. In this particular conchord I have formalised the speech patterns into cantos of five equal ten-lined speeches of iambic pentameter, like the Odes of John Keats. Its form has its origing in the chaunt royale of the trouadours. Between these dramatic scenes I have placed traditional dances & composed settl’d lyrics for the normally extemporized Maltese singing art of ghana. I have supplied no melodies or music, but having stuck rigidly to the metrical rules – quatrains of 8-7-8-7 syllables, with a rhyme scheme of ABCB – I am sure most of the traditional ghama melodies may be attached to my words. At all times I had G.A. Vassallo’s dictum ringing in my ears, whic states, ‘any poem, written in Maltese, that did not employ the octosyllabic verse is, at least in its form, spurious… & will never become popular.’ I was also inspired in my work with the ghana by another Maltese author & linguist, Guze Aqulina, who stated; ‘some quatrains contain fine images that, handled by a skilled writer, could be woven into verse that was better expressed & more varied in texture.‘

For the Maltese I hope that reading through these poems will grant just a portion of the pleasure I had in writing them. Malta & Gozo might be small islands, but they have continental-sized depths & have dipped their sisterly toes into every sub-stratum of history since the dawn of Human consciousness. They are also exceedingly fortuitous in possessing scenes of unrivalled natural beauty, & are peopled by sentinel beings of warmth, kindess & gentle jocundity. To any accusation that I am not Maltese I would reply that I take my art as seriously as the early medieval Icelandic skalds, who touted their literary wares at all the courts of Europe. Whether my work will ever be extolled like theirs, I leave to taste & time, but hope to be remembered at least as an English poet who revelled in the near-perfect conditions that one needs to write poetry, in which Malta, & Gozo especially, possess in abundance.

San Julian

03/12/2020

Brunanburh, Beowulf & Egil Skallagrimsson

Brunanburh! Brunanburh! Brunanburh! This antique name was once attached to an Anglo-Saxon fortification, in whose locality was fought one of the most important battles in British history (937 AD). A massive showdown, it saw King Athelstan of England face off against a grand alliance of Scots, Vikings & the ‘Northern Welsh’ of Cumbria & Galloway. This confederacy had been galvanized into action by a young Viking prince called Analf Guthfrithson. Normally based in Dublin, Analf had momentarily managed to unite the entire Viking world behind him in an attempt to wrestle back their former control over England which had been lost to Athelstan’s grandfather, Alfred the Great. Despite such powerful forces arrayed against them, the Battle of Brunanburh was a comprehensive victory for the Saxons, since which day the borders of Britain’s three nations have been more or less constant. One could fairly admit that the Battle of Brunanburh was the moment when the British Isles were truly born.

The first mention of Brunanburh in the annals comes within the pages of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, that wonderful storehouse of early English history without which the Dark Ages would have been much, much darker. The entry for 937 is actually one of the most famous pieces of Anglo-Saxon poetry, the first & best of a series composed throughout the 10th century. Most entries in the ASC are written in rather mundane prose, but the rendering of certain events in poetry would naturally amplify their cultural importance. It is only through the Pegasus-flight of the poetic voice that humanity may truly record the incredible passions felt in the most turbulent of times. A fine example is the poetry of Wilfred Owen, without whose words our ability to feel the sensations inspired by the trenches of World War One would be much diminished. Similarly, the composer of the Brunanburh poem manages to reflect with consummate skill the spirit of battle, basing his words upon what appears to be genuine eye-witness accuracy.

In this year King Aethelstan, Lord of warriors,

Ring-giver to men, and his brother also,

Prince Eadmund, won eternal glory

In battle with sword edges

Around Brunanburh. They split the shield-wall,

They hewed battle shields with the remnants of hammers.

The sons of Eadweard,

It was only befitting their noble descent

From their ancestors that they should often

Defend their land in battle against each hostile people,

Horde and home. The enemy perished,

Scots men and seamen,

Fated they fell. The field flowed

With blood of warriors, from sun up

In the morning, when the glorious star

Glided over the earth, God’s bright candle,

Eternal lord, till that noble creation

Sank to its seat. There lay many a warrior

By spears destroyed; Northern men

Shot over shield, likewise Scottish as well,

Weary, war sated.

The West-Saxons pushed onward

All day; in troops they pursued the hostile people.

They hewed the fugitive grievously from behind

With swords sharp from the grinding.

The Mercians did not refuse hard hand-play

To any warrior

Who came with Anlaf over the sea-surge

In the bosom of a ship, those who sought land,

Fated to fight. Five lay dead

On the battle-field, young kings,

Put to sleep by swords, likewise also seven

Of Anlaf’s earls, countless of the army,

Sailors and Scots. There the North-men’s chief was put

To flight, by need constrained

To the prow of a ship with little company:

He pressed the ship afloat, the king went out

On the dusky flood-tide, he saved his life.

Likewise, there also the old campaigner

Through flight came

To his own region in the north–Constantine–

Hoary warrior. He had no reason to exult

The great meeting; he was of his kinsmen bereft,

Friends fell on the battle-field,

Killed at strife: even his son, young in battle, he left

In the place of slaughter, ground to pieces with wounds.

That grizzle-haired warrior had no

Reason to boast of sword-slaughter,

Old deceitful one, no more did Anlaf;

With their remnant of an army they had no reason to

Laugh that they were better in deed of war

In battle-field–collision of banners,

Encounter of spears, encounter of men,

Trading of blows–when they played against

The sons of Eadweard on the battle field.

Departed then the Northmen in nailed ships.

The dejected survivors of the battle,

Sought Dublin over the deep water,

Over Dinges mere

To return to Ireland, ashamed in spirit.

Likewise the brothers, both together,

King and Prince, sought their home,

West-Saxon land, exultant from battle.

They left behind them, to enjoy the corpses,

The dark coated one, the dark horny-beaked raven

And the dusky-coated one,

The eagle white from behind, to partake of carrion,

Greedy war-hawk, and that gray animal

The wolf in the forest.

Never was there more slaughter

On this island, never yet as many

People killed before this

With sword’s edge: never according to those who tell us

From books, old wisemen,

Since from the east Angles & Saxons came up

Over the broad sea. Britain they sought,

Proud war-smiths who overcame the Welsh,

Glorious warriors they took hold of the land.

Leaving aside for a moment the quest for the battlefield’s location (Burnley), I would now like to turn our digressional attention to a certain Egil Skallagrimsson. This guy is a true Icelandic legend, a warrior-poet of the 10th century who is the movie-star of the anonymously-penned 13th century Egil’s Saga. For me, he is the leading contender for authorship of the poem that was used by the Anglo-Saxon Chroniclers for 937 AD.

Egil was a widely praised poet – he composed his first at the tender age of three – & could well have been commissioned by Athelstan to compose a triumphant piece of propaganda. We know the poem was more or less contemporary to the battle, finding itself inserted into the ASC at least as early as 955, when it was written into the so-called “Parker Chronicle” ( Whitelock 1955). Egil was the best poet of his time & the poem is clearly the best in the Chronicle. Alistair Campbell (1938) notices how the original version of the poem contained many, ‘non-west saxon & archaic forms’ & declares, ‘who the poet was is impossible to say.’ He does, however, go on to describe the spirit of the poet, as in;

Although he owes much to his predecessors, the poet of the Battle of Brunanburh is by no means without merits of his own. He uses the conventional diction neatly & cleverly, & never becomes swamped in phrases… the two feelings which breathe through the poem are scorn & exhultation, & they are perfectly expressed. Lastly, despite the wealth of poetic diction at his command, he can be, at times, astonishingly simple & direct; the chief example of this is the description of battle from 20 to 40, where there is little repetition, & nearly every half-line advances the narrative… the poets subjects are the praise of heroes & the glory of victory… his work is a natural product of his age, an age of national triumph, antiquarian interest, & literary enthusiaism

My gut, litological instinct tells me that Egil was the author of the poem, based undeniable facts such as;

A – Egil fought at Brunanburh

His presence at the battle is without question & recorded extensively in the saga of his life by Snorri Sturlsson

B – Egil stayed at Athelstan’s court

A year or two after the battle, Egil returned to Athelstan’s court, & I believe it was at this time in & in the post-Brunanburh climate that the poem was produced. Although giving very little detail of Egil’s visit to Athelstan, the Saga definitely places him there, as in;

During the second winter that he was living at Borg after Skallagrim’s death Egil became melancholy, and this was more marked as the winter wore on. And when summer came, Egil let it be known that he meant to make ready his ship for a voyage out in the summer. He then got a crew. He purposed to sail to England. They were thirty men on the ship. Asgerdr remained behind, and took charge of the house. Egil’s purpose was to seek king Athelstan and look after the promise that he had made to Egil at their last parting.

It was late ere Egil was ready, and when he put to sea, the winds delayed him. Autumn then came on, and rough weather set in. They sailed past the north coast of the Orkneys. Egil would not put in there, for he thought king Eric’s power would be supreme all over the islands. Then they sailed southwards past Scotland, and had great storms and cross winds. Weathering the Scotch coast they held on southwards along England; but on the evening of a day, as darkness came on, it blew a gale. Before they were aware, breakers were both seaward and ahead. There was nothing for it but to make for land, and this they did. Under sail they ran ashore, and came to land at Humber-mouth. All the men were saved, and most of the cargo, but as for the ship, that was broken to pieces.

When they found men to speak with, they learnt these tidings, which Egil thought good, that with king Athelstan all was well and with his kingdom… in that same summer when Egil had come to England these tidings were heard from Norway, that Eric Allwise was dead, but the king’s stewards had taken his inheritance, and claimed it for the king. These tidings when Arinbjorn and Thorstein heard, they resolved that Thorstein should go east and see after the inheritance.

So when spring came on and men made ready their ships who meant to travel from land to land, then Thorstein went south to London, and there found king Athelstan. He produced tokens and a message from Arinbjorn to the king and also to Egil, that he might be his advocate with the king, so that king Athelstan might send a message from himself to king Hacon, his foster-son, advising that Thorstein should get his inheritance and possessions in Norway. King Athelstan was easily persuaded to this, because Arinbjorn was known to him for good.

Then came Egil also to speak with king Athelstan, and told him his intention.

‘I wish this summer,’ said he, ‘to go eastwards to Norway and see after the property of which king Eric and Bergonund robbed me. Atli the Short, Bergonund’s brother, is now in possession. I know that, if a message of yours be added, I shall get law in this matter.’

The king said that Egil should rule his own goings. ‘But best, methinks, were it,’ he said, ‘for thee to be with me and be made defender of my land and command my army. I will promote thee to great honour.’

Egil answered: ‘This offer I deem most desirable to take. I will say yea to it and not nay. Yet have I first to go to Iceland, and see after my wife and the property that I have there.’

King Athelstan gave then to Egil a good merchant-ship and a cargo therewith; there was aboard for lading wheat and honey, and much money’s worth in other wares. And when Egil made ready his ship for sea, then Thorstein Eric’s son settled to go with him, he of whom mention was made before, who was afterwards called Thora’s son. And when they were ready they sailed, king Athelstan and Egil parting with much friendship.

C – The poem is Bookish

Where JD Niles notices that scholars have, ‘drawn attention to the poem’s studied artistry, including its use of syntactic variation, studied antithesis, aural patterning, and an array of rhetorical figures that may be patterned on Latin models,’ Campbell (1938) tells us, ‘the poem is remarkably ‘correct’ in metre : that is to say, its half-verses are constructed with regard to the limitations, & bound together by alliteration with regard to laws, which are found in the earlier Old English poetry… the diction is almost entirely composed of elements to be found in earlier poems…. a large number of word s & expression which forcibly recall the older poetry.’ We must also observe that the poem does not rhyme, with Campbell stating, ‘as a final instance of the conservative nature of the versification of the Battle of Brunanburh, the absence of rhyme must be mentioned.’

I am a poet myself, & I understand the very tidings of poetic construction. Scholars have observed how the Brunanburh poem is packed full of direct lifts, or half-lifts, from the corpus of Anglo-Saxon literature. To my mind, although Egil would have been fluent in Old English, he may not have been so observant in its literature. To remedy this, during the composition of the Brunanburh poem I believe he made use of Athelstan’s library, in order to paint his epic, panygerical pastiche. Where Campbell tells us ‘it is evident that the Battle of Brunanburh shows no changes in the structure of the half-line : all its types can be paralleled in the older poetry, & practically all of them in Beowulf,’ in the poem, 21 half-lines occur identically in other OE poems, such as

eorla dryhten (Beowulf)

on lides bosme (Genesis)

wulf on wealde (Judith)

While 23 half-lines are nigh identical, as in;

faege feollan (Beowulf) = faege gefealled

on folcstede (Judith) = on dam folcstede

bone sweartan hraefn (Soul & body) = bonne se swearta hrefen

D – The poem is Skaldic

In the 10th century, the Icelandic poets – the Skalds – were the best in Europe, & their professional services were sought by many a wealthy king. That the Brunanburh poem has Skaldic roots is supported by JD Niles, who tells us;